Fraser Hibbitt reflects on ‘A Letter From A Birmingham Jail’ for the Carl Kruse Blog on MLK Day 2022

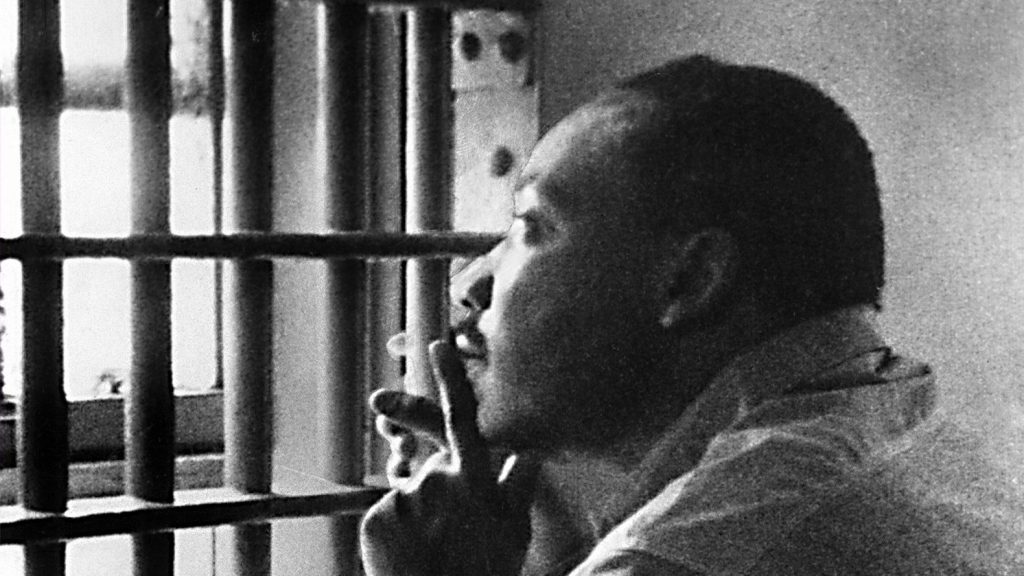

Embodied love must act: it is how it measures time. Reading Martin Luther King’s ‘Letter from a Birmingham Jail’ is to meet the weight of words – words that hold a history of strife, tension, and the fight for justice. Here, these all too familiar words find their significance, penetrating through the years, pregnant for as long as they are read. This is the culmination of aesthetics – to have the word placed in the right order at the right time for the right effect. And from King’s prison bound hand, we realize he couldn’t possibly ever be in a prison, nor, in fact, that he has passed away. It is in these words that an access to the words themselves become explicit. Many others could possibly write the same, even with the same eloquence, but where would the words ring from?

With this example, we are reminded. We remember how to think about justice, about immorality. It is not that we forget – it perhaps sleeps, or grows jaded by uneventfulness, nevertheless it is still there. ‘While confined here in Birmingham city jail…’ the letter opens. He is confined there because injustice is there – he couldn’t sit idly by knowing this. If we pause here, in our freedom to pause, we will be doing him some justice. If we are reading it of our own volition in the comfort of our house, library, or coffee shop, we can feel what freedom means – how essential it is in feeding a meaningful response to the world. We can, by extension, perhaps begin to glimpse the terrible opposite of this condition.

To reflect here on what this means proves worth the time; taking time to embody the idea, taking the words in, is an act of respect – waiting on the words for this type of revelation is part of the remembrance. The fluency with which his words fall on the page come from a lifetime of thought, of patient study. For him the threshold was reached in which thought had to be combined with action if it were to be a thought at all – if it were to have any meaning at all. When he writes his rhetorical figures, they appear as actions on the page.

The mellifluous lines and measured confidence in which King responds to his critics is exacting without the bitterness of hostility. Every line is an example of a kind of freedom, and we must constantly remind ourselves during the read that he is in prison. His presence on the page is incarnate, and it cannot help but make us reflect on our own position, our own thoughts and our own presence.

King was jailed for joining a peaceful protest, a sit-in. It is with this fact that we have cause to wonder about the power of the body. The weight of the body cannot be dismissed and it speaks forcefully, implicitly, and without dissimulation. It is for the body too that King protested for. He knew, and states explicitly in the letter, the fates that attended the African-American body. The toll of being dismissed, of being placed apart from common existence. This leads the body to extremes: to violence or embittered self-hatred. This is why King used his body and showed its power – its power to reconcile and share common experience.

Over half a century later, the words, and the spirit behind those words, have not dampened. A free man was writing from a prison – this paradox demands a thoughtful reading. I have said to wait on his words, and yet so much of his message is about not waiting, about taking time into your own hands. There will never be a time where things are ripe for questioning, for demanding, for acknowledgment. It cuts through the matter – there is a time for you when you consider yourself.

For King, the disappointment he felt on hearing his fellow clergymen call his actions “unwise and untimely” struck the creative spark for this letter. With grace, he answered, but answered to more than the addressee. Implicit in the letter, the pursuit of justice across all boundaries persists as the united core of humanity. His answer is an answer to injustice everywhere. Things have, of course, changed, but the message to not withhold, to be perceptive of the ‘stagnant society’ which he saw and fought against, still stands. King dreamt of a creative and loving society, and strove for those ends, ends that have begun to flower since he departed; we still know him by the soil he left behind.

============================

Homepage: The Carl Kruse Nonprofits Blog

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT org

Other reflections on Martin Luther King on the blog are here, over here, also here and finally here.

Also find Carl Kruse over at Goodreads.

Thank you for this.