By Asia Leonardi, writing for the Carl Kruse blog

The story of Heinrich Schliemann and his discovery of Troy, has all the elements of a children’s adventure novel and gives archeology that passionate and not very academic character that feeds the dreams of kids at that tender age when they fantasize about their future.

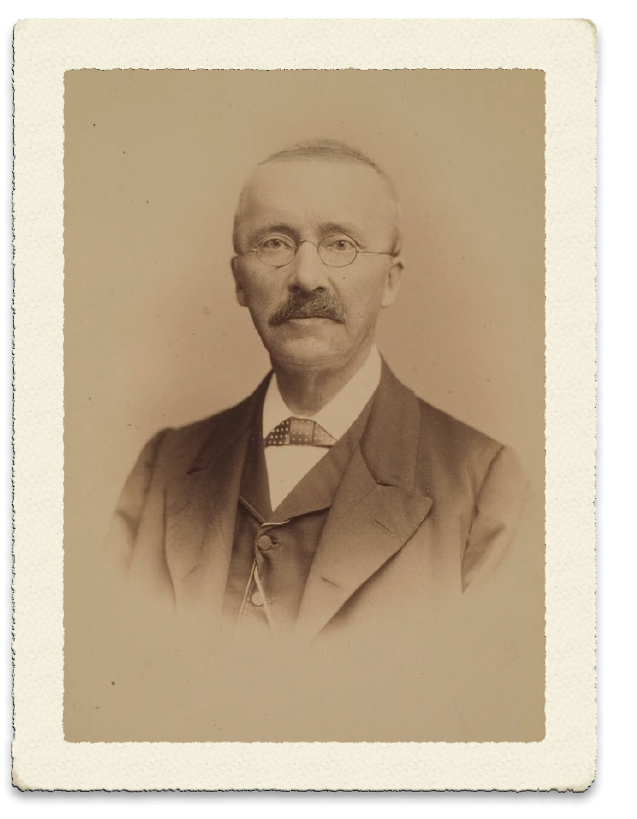

Schliemann was born on January 6, 1822, in Neubukow, Germany into a family of modest means. His father, a Protestant pastor with a humanist background, through the tales of fables and legends of the past, and above all through the reading of Homeric poems, made little Heinrich passionate about ancient civilizations and the extraordinary exploits of Homeric heroes.

In his autobiography, Schliemann recounts that during Christmas 1829, when he was seven years old, his father gave him an illustrated history of the world and on a page depicting Aeneas fleeing from the burning city, with his old father on his shoulders and his little son held by the hand, he stood staring at the city. Schliemann looked at the imposing walls, the Scea Gate, and was deeply impressed.

“Was that the city of Troy?” he asked his father, who nodded. “And everything is destroyed and you don’t know where it was?” he asked again. Again his father said yes. “When I grow up I will find it, the city of Troy”, Schliemann said with conviction.

After his mother’s death, his father entrusted him to his uncle so that he could provide him with adequate education, which Schliemann could only attend for a short period due to his parent’s growing financial problems.

At the age of fourteen he was forced to abandon his studies and work in a grocery store in Furstenberg. Between herring, milk, salt, and eighteen hours a day, he forgot everything he had studied and stopped thinking of those ancient heroes who had so fascinated him. The harsh reality had supplanted his boyish dreams, until one day, in the shop, a drunk miller began to loudly speak verses that were familiar to him. They were those of the Iliad. Schliemann collected the few coins he could find by rummaging in his pockets and offered them to the man so that he could continue to recite the words of Homer.

The legendary city of Troy returned to haunt him.

A few years later, thanks to the recommendations of a family friend, he found work first as a doorman and then as a delivery boy in Amsterdam. That was the time when he began to learn languages in a poor, cold attic. He was able to develop a method for learning Dutch, Portuguese, Italian, English, French, and Russian in just two years.

Thanks to his intuition and his brilliant personality he became first a merchant and then a successful

trader.

In 1846, at the age of twenty-four, he went to St. Petersburg as an agent for his firm. A year later he founded his own trading house.

In 1850 he set sail for the United States and amassed a small fortune by lending money to gold miners. After undergoing a fraud trial, he returned to St. Petersburg where he married the daughter of a wealthy lawyer. The Crimean War was a tremendous source of income for Schliemann as he supplied the Tsar’s troops with provisions and war material. In those same years, he began studying other languages such as Arabic, ancient Greek, and Hebrew.

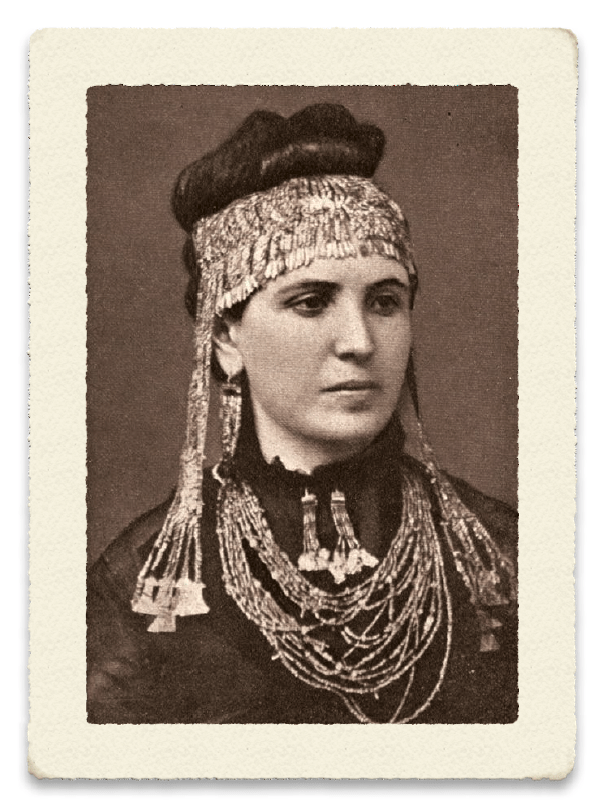

1868 was a turning point: he decided to abandon business to pursue his youthful dreams. After divorcing his first wife, he married the Greek Sophia Engastromena with whom he had two children, Andromache

and Agamemnon. He traveled between China, Japan, Italy, and Greece, until finally arriving in Turkey, determined to find the legendary city of Ilium.

During Schliemann’s time, Homeric work was considered, even by a large part of the academic community, to be almost fiction, nothing more than myths and legends enhanced by the talent of a great poet. But for Schliemann the stories of the heroes Achilles, Patroclus, Agamemnon,

Menelaus, and Aeneas, the loves, the poisons, the bloodshed in battle, the glorious deeds narrated in the Homeric poems, all this was not the result of a marvelous fantasy, but it was about history and historical characters.

Official archeology, at that time, indicated the village of Bunarbashi as a probable site of Troy, if it ever really existed. The motivation that justified the identification with this site was the presence of two fountains in the area. In Book XXII of the Iliad, verses 147-152 we read:

“ […] and (they) came to the two fair-flowing fountains, where well up the two springs that feed eddying Scamander. The one floweth with warm water, and round about a smoke [150] goeth up therefrom as it were from a blazing fire, while the Troy’s ruins other even in summer floweth forth cold as hail or chill snow or ice that water formeth.”

Schliemann first tried to verify the presence of these fountains and found that there were not only two but thirty-four. Furthermore, while Homer spoke of a source of cold water and one of hot water, Schliemann measuring the temperature of all of them found that they had a constant temperature of 17.5 degrees centigrade.

Looking at the plain that stretched before his eyes from the Bunarbashi site he saw that the coast was at least three hours’ walk, difficult to reconcile with what Homer had narrated since his heroes could run several times a day from the ships to the city. Basically, during the first day of battle, described from the second to the seventh canto of the Iliad, if Troy had hidden under Bunarbashi, the Achaeans would have covered at least 84 km in nine hours of battle.

Going then to analyze the verses of the Iliad in which the terrible fight between Achilles and Hector is told, we read that the latter fled from his pursuer and “circled the fortress of Priam three times”. Schliemann, therefore, tried to do the same path around what supposedly should have been the fortress, but the slope was so steep that in the end he was forced to go down on all fours. Climbing on it three times “with quick feet” seemed rather far-fetched.

And there were no ruins and terracotta fragments that the site should have abounded.

Everything suggested that Bunarbashi’s theory was incorrect. Just a two-hour walk north, however, not far from the coast, was Hissarlik. When Schliemann found himself on top of that hill he knew he was in the right place. Here the chase between Hector and Achilles did not seem improbable, they would have traveled 15 km, completing the city three times.

He found no fountains there, but as already

described by Frank Calvert, who years earlier had

theorized the possibility of identifying Troy in Hissarlik, hot springs appeared and disappeared in that volcanic territory in a short time. Therefore that type of data, which had been fundamental to discard the

Bunarbashi hypothesis, now turned out to be completely irrelevant.

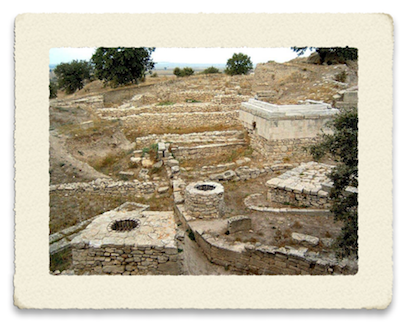

Schliemann was convinced, Troy was down there. Excavations began in April 1870, arriving in 1871 to involve about a hundred workers.

The various layers of the city.

He carried on his work with feverish obsession, overcoming any obstacle, from malarial fevers to the poor reliability of his workers, from the lack of drinking water to the open hostility of the academic world, which

never missed an opportunity to mock his company.

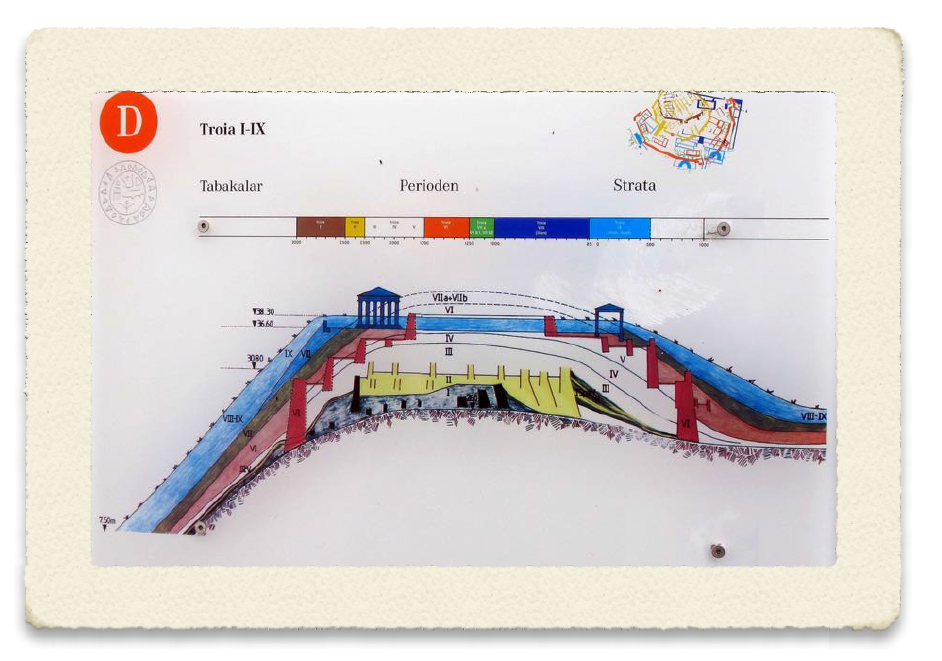

He began to demolish the walls of a later period, he found more and more furnishings and terracotta, testifying to the wealth of the city. Under the walls of the New Ilium, he found another layer, under which he found yet another, and so on. Layers and layers inhabited in the most diverse eras.

In one year he discovered seven cities layered on top of each other and later found two more. The oldest part was prehistoric, in the second and third layers, there were traces of a fire and the remains of massive

ramparts and an imposing gate. The Priamo palace and the Scea Gate. It was all true then.

Troy was history and it was under his eyes.

The news went around the world and so much was the dismay of the official archeology.

After having excavated 250,000 cubic meters of earth, Schliemann felt more than satisfied and thought he had found everything significant there was to find. The last day of excavations, before a temporary stop, was therefore set for June 15, 1873, but the unimaginable happened just the day before. They were twenty-eight feet deep along the perimeter of what must have been Priam’s palace, and as usual, he and his wife supervised the work of the workers, when suddenly he noticed something that caught his attention. He hastily dismissed the workers – whom he did not trust in any way – and asked his wife to bring her shawl. He began to dig frantically to unearth something that was wedged under some boulders that hung threateningly over his head and that were gradually becoming less secure.

And behold, in the shawl that his wife had brought he placed gold cups, silver vases, and precious diadems. It was the gold of Priam, one of the most powerful kings of antiquity, buried for three thousand years under the ruins of seven destroyed kingdoms. Schliemann collected the precious treasure and took it out of Turkey without permission. For this reason, his excavation concession was revoked, the Ottoman government asked him to give him part of the discovery and imprisoned the officer in charge of supervising the excavations.

Schliemann subsequently sent part of the treasure to the Ottoman government in exchange for permission to resume excavations in Troy. The part that remained to him was purchased in 1880 by the Imperial Museums in Berlin and exhibited at the Pergamon Museum, from which they were taken in 1945 by the Red Army and probably sold on the black market. Some of the objects reappeared in 1993 in the Pushkin Museum in Moscow, where a part of them still stand today, while the remainder are exhibited at the Hermitage in St. Petersburg.

Only after Schliemann’s death was it shown that Troy was not in the second or third layer, but in the sixth from the bottom and that what he had found was not Priam’s treasure but that belonging to a king of a thousand years older. old, but Schliemann’s fable had nevertheless been made a reality by himself, and consigned Troy to history.

============

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

Another take on Schliemann here.

Last blog entry It’s Time to Dance!

For a different type of discovery check out the Voyager Golden Records.

Carl Kruse is also on Dwell.

What a fabulous story and what a big set of cojones Mr. Schliemann had to pursue his fascination with Troy.

A giant pair my dear Tatyana. 🙂

Carl Kruse

Was Schliemann mostly self-funded? I can’t imagine where he would get money to pursue what at the time could have only been thought of as a harebrained scheme.

I believe he was partly self-funded but did have some other sources of support.

Carl Kruse