by Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse blog

It is strange that some of the most harrowing passages in Mr. Bessel Van der Kolk’s The Body Keeps the Score are excited from dry facts. When he writes of the revenge stories told to him by his Vietnam veterans, the savage and brutal events pierce the mind. However, on a page showing brain scans there appears a fact of experiment and study which is so shocking; it amounts to nothing more than entrapment within one’s skull.

It is that the traumatized patient lives against themselves, destined to re-feel the terror of trauma. The proof, as shown in the brain scan, is an abstract rendering of this fact. Nonetheless, it is something of a haunting. A continual haunting of the senses, where the body relives the horrible burden of the past. There is completed repetition without the satisfaction of rest, without the processing of the event which has passed. The body is morphed by events so terrible to a repetitious fount of suffering.

The story of understanding and treating trauma reveals both the shortcomings of psychological treatments and of the pharmacological revolution. It has also greatly improved our understanding of the mind-body relationship through forcing psychiatry to listen, and not avoid, the horrible instances of experience that are rife in society; the wars that linger in the body, and the homes which are places of violation.

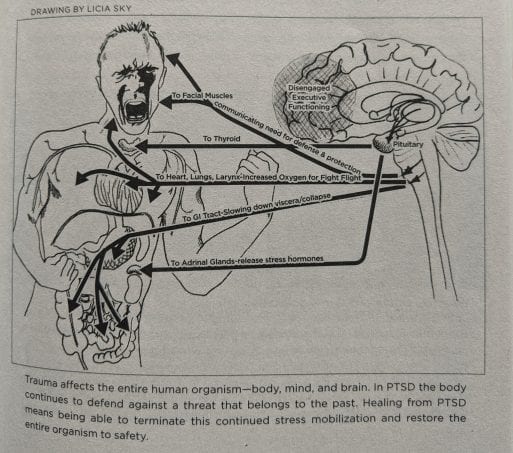

Image for Van der Kolk’s The Body Keeps the Score – “a traumatized individual’s attempts to maintain control over unbearable physiological reactions can result in a whole range of physical symptoms and autoimmune diseases.”

Psychoanalysis, despite its preoccupation with memory, could not grasp the instability of the body affected by trauma. Although psychoanalysis became aware of humanities proneness to ‘re-living trauma’, it did not realize that talking and understanding doesn’t necessarily help; in fact, in many cases, replaying the events from the psychoanalyst’s sofa only reinforced the hold trauma kept on the body. Psychoanalysis underwent criticism in the 1960s and a new approach based on experiment was beginning to take off in psychology.

Making sense of suffering is an ongoing, fluid process. However, in the world of psychology, such a conception of traumatic suffering was not immediately obvious. The desire to define and objectify suffering was a strain of thought within the machinations of the psychiatric world that gave birth to the pharmacological revolution. Van der Kolk describes this tendency as a change of perception in the psychologically minded, where suffering changed ‘from infinitely variable expressions of intolerable feelings and relationships to a brain-disease model of discrete “disorders”’; something akin to saying that the personal attention giving by someone like Carl Jung was replaced by an abstract statement.

These are disorders which could be analyzed and, hopefully, reversed. If the problem is a chemical imbalance, then all is needed is the right drug. Under this frame of thought, pharmacology had a bright start. Anti-psychotic drugs played a decisive factor in reducing the vast numbers of suffering patients in mental hospitals, and opening them up to new vistas of experience in the outside world.

The triumph of pharmacology led to a new conception of viewing disorders: maintaining chemical equilibriums. The problem, Van der Kolk found, was that administering the drugs in this impersonal manner deflected attention from any underlying issues. The complexity of the mind and body connection are reduced to a chemical composition and are therefore alienating to an idea of self-hood. Mood and self-hood are observed objectively as something to be treated by a foreign entity; it doesn’t require the reflective, spontaneous, and integrative role one must take on to feel whole.

If we take the ‘patient’ to be in the position of supplication, then two aspects of this new conception of diagnostics become apparent. Firstly, the patient needs their will to be molded and repaired by an external will and, secondly, a kind of transmutation occurs wherein the patient is turned from a subject to an object.

Administered from above. Van der Kolk would refer to this as a ‘top-down’ method of treatment. It was seen in the breakthrough of pharmacology as a panacea, and, in fact, still plays a reputable role in treatment. The problem lies in not conceiving drugs as an adjunct to revitalizing the spirit. If the drugs can jump the first hurdle, they cannot finish the race. This is what the study and patient effort towards understanding trauma has revealed; or, as the title of Van der Kolk’s book puts it: the body holds the score. Drugs, as of yet, do not realign the neural pathways of the brain, although they may put one in a position to do so. This is the salient point with trauma as the imprint it leaves on the body and mind needs to be engaged with. If the ‘mode of being’ still operates under the stress of trauma, as its repetitious nature shows, then a ‘bottom-up’ approach must also be entertained.

A ‘bottom-up’ approach is the task of re-founding the body, re-engaging and understanding how the body relates to the world and other people. This is a continual process of emerging out of the habitual trauma-ridden processes of the mind into new and unexpected vistas of experience. The utterly life-shattering imprint of trauma exiles the soul from curiosity, spontaneity and meaning. The fight back from trauma is a struggle between the life-affirming and the life-denying.

This psychological process explains why drugs alone cannot win the fight. There is needed a growing sense of self, of association, and understanding. These are things that self-willed action and engagement foster; action takes back the body. A person on the mend learns much about action and behavior, about the right actions and behaviors which ameliorate their lives. In learning again, it becomes quite clear what actions keep the soul in turmoil and which bring understanding and release.

Van der Kolk’s book shows a fascinated story of how trauma has become to be understood in our time; how trauma has been culturally treated and what this tells us about how we have felt about society’s ‘shadow’. It is a story of varied psychological studies coming together, some by chance, and others by consistent troubleshooting, to overcome prejudices; the fluctuation between the impersonal administering of drugs and the cooperative experiments between patient and psychiatrist tells us something of how psychiatry has viewed, and learnt from, the patient.

Learning from the patient is a consistent tool that Van der Kolk highlights in his book. In fact, the book is dedicated to the patients themselves. It is by the consistent ability to view illness as part of humanity, to see humanity as disordered, that has amassed our understanding of lived experience. And so it appears, when the psychiatrist keeps humanity as their subject, the patient can regain what was so unjustly taken away from them.

============

The Carl Kruse blog homepage.

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com.

Other articles by Fraser Hibbitt include: Stoicism, Houses of Great Minds, and a Summer Conversation Between Oakley and Eagerton.

Also find Carl Kruse on Vator here.

I read the Body Keeps The Score some time ago and now I would like to read it again.

Highly recomended Tinky!

Carl Kruse

It’s out of the question.