by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Blog

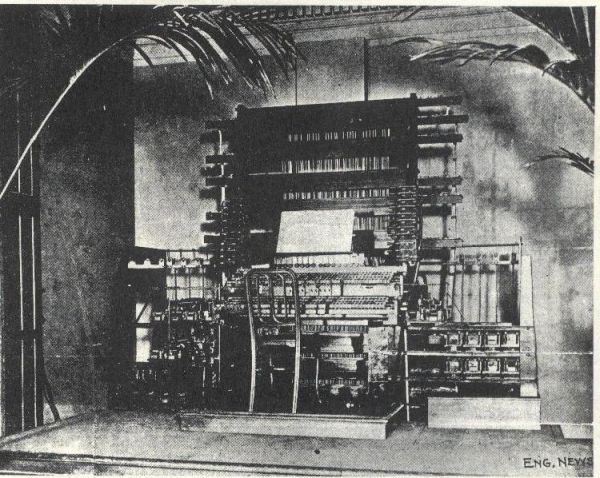

In 1896, Thaddeus Cahill, of Iowa, USA, completed the machine that he had been working on since completing his degree in the physics of music at the Oberlin Conservatory in Ohio.

This machine was to transform the production and distribution of music, and Cahill’s ambitious invention began a revolution in music creation. This mysterious machine was called the harmonium (or Dynaphone), and was, as such, a sort of electronic organ which transmitted sound through horn speakers via numerous wires connected to the device. By including so-called ‘tonewheels’, the primary of which were connected to each single note and the secondary to add further harmonics to these notes, Cahill was able to produce a beautiful and clear sound with the instrument. The additions of extra keyboards, stoppers (somewhat akin to those of an organ), and foot pedals (like those used on a piano to extend the life of a note or chord), the sounds of the cello, flute, clarinet, and other woodwind instruments were reproduced through the Telharmonium. In total, the machine had 153 keys.

Sadly, Cahill’s vision with the Telharmonium was a flop. Despite some initial interest in smaller performances with the instrument, and some more notable ones in New York, one of which was attended by no other than Mark Twain (1906), after 1912, public intrigue in the instrument had waned so far that it was irretrievable. There are many reasons as to why this could have been. For one, the instrument was so huge, with all its wires and the sheer size and weight of the machine itself (the Mark I was 7 tons, and Marks II and III no less than 210 tons), which would have made it both difficult to shift and very difficult to set up. Furthermore, what with the downright absurd quantity of energy required (in the form of electric dynamos, the first electric generators used in industrial settings) to produce strong enough electric signals for the instrument to work, it was expensive to run; the instrument needed around 671 kilowatts of power. Another rather humorous issue that arose during the use of the machine was the crossing of channels or circuits associated with the instrument and telephone lines in the vicinity (this phenomenon is known as crosstalk). This ‘crosstalk’ led to some telephone conversations being interrupted with the music produced by the Telharmonium.

But, despite all of these significant problems, perhaps electronic music really was just a ‘one-hit wonder’. What with the quickly approaching first World War (beginning in 1914), the eruption of the jazz scene in New York (The Original Dixieland Band was one of the first jazz bands to be recorded at the New York nightclub), and the obvious inaccessibility of such an instrument (the Telharmonium was retailed by Cahill for $200,000 dollars (approx. $5,514,000 today)), electronic music faded into the background for some time before its reprisal in the 1930s.

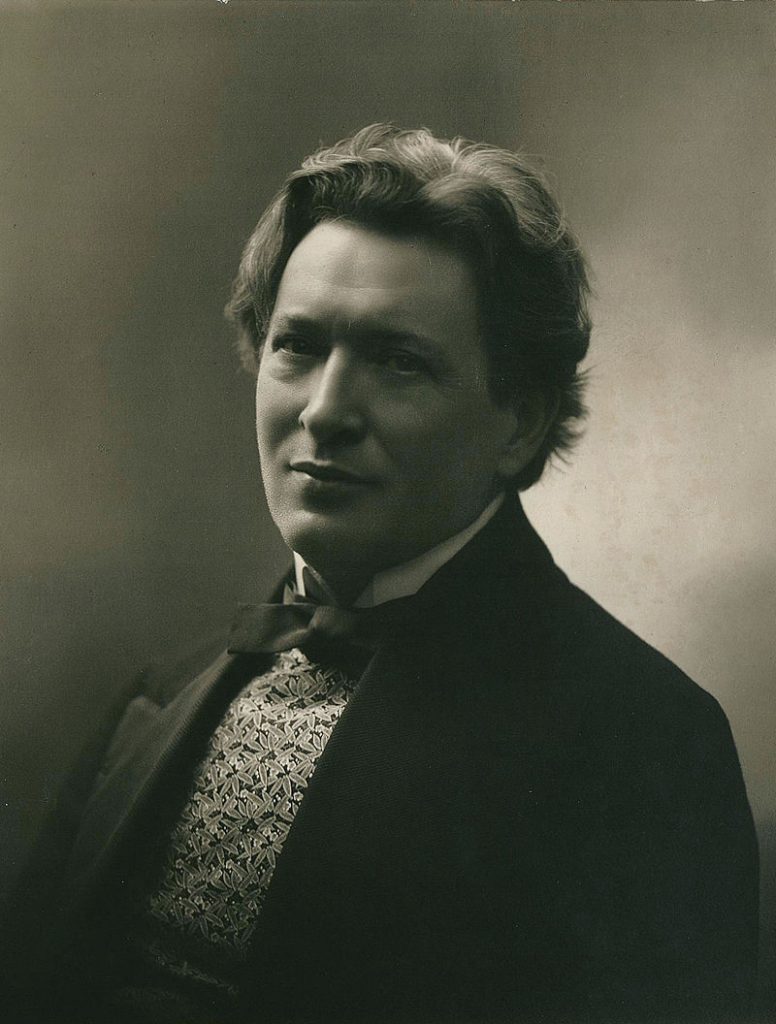

However, we shouldn’t shade over other aspects of the electronic music revolution during the early twentieth century. Musical prodigy Ferruccio Busoni, who corresponded extensively with the Italian Futurist movement, was greatly intrigued by the possibilities of innovative music technology; in 1888, he began nurturing the idea of microtones, and even drafted some plans in the 1920s for an instrument that would be able to produce thirds of tones (which he called a Dritteltonharmonium). This machine was never created, but Busoni’s progressive musical manifesto, Sketch of a New Esthetic of Music (1907) became the inspiration for many later composers who wanted to foray deeper into an alternative philosophy and practice of music. Busoni’s discussion of the microtone is fascinating, and I would like to elaborate on the term briefly. A microtone is basically any interval between notes of less than a semitone, so, if we look to a piano, a microtone is any note that comes between each note on a regularly tuned keyboard. The term can include any music that might stray from the equal temperament (the division of an octave in 12 equally spaced notes) found in the Western twelve-tone musical formula. So…could we then deduce that Busoni’s foray away from standard forms of Western music was influential in the quest to decentralize the West from having a precedent over the popular and classical musical scene? Who knows.

Ferruccio Busoni in 1913. Photo from Wikipedia.

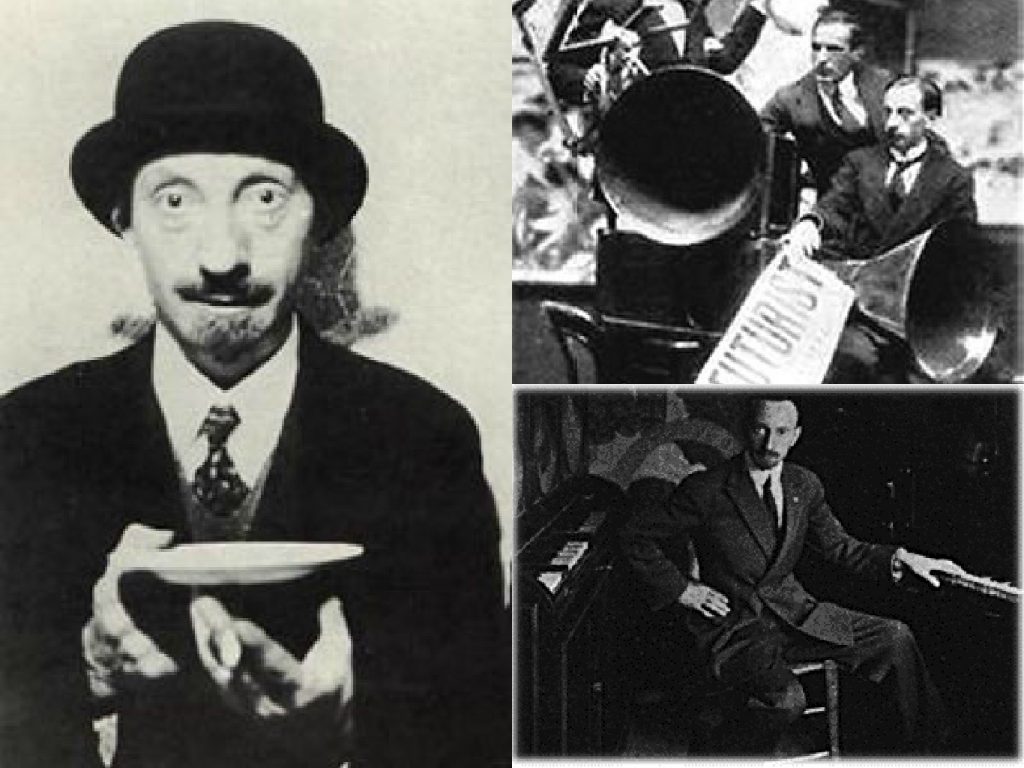

Luigi Russolo, the Italian Futurist composer and painter, produced several experimental instruments intended to recreate the sounds of machinery and other noises of industrialism in the early 20th century. Russolo also wrote the instrumental text The Art of Noises (1913) which propounds the importance of incorporating the changing exterior world of industry and urbanization into music. Russolo reasoned that, while in ‘ancient’ times the world was ‘silent’, the development of machinery throughout the world led to the creation of ‘noise’, and, thus, he suggests that, as human ears are now acquainted with the ‘noise’ of the urban world, it is important to acknowledge this ‘noise’ in popular music so as to replicate the complexity of the sounds we encounter in modern life. Russolo also prophesized the creation of new technology that would be able to produce an ‘infinite variety of noise-sounds’ (Warner, Daniel; Cox, Christoph (2004). Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music. London: Continiuum International Publishing Group LTD. pp. 11). Russolo was not wrong with his predictions. Many composers post-Russolo and other Futurist composers alive during his time continued to progress with new technology in music, and, notably, electrical recording finally became possible in 1925. Additionally, the theremin, patented by Soviet inventor Leon Theremin in 1928, was an electronic instrument controlled by the ‘thereminist’ through the use of proximity sensors (thus the performer does not physically touch the instrument to play it). This instrument was used throughout the 20th century in concert and popular music.

From the 1940s onwards, some important changes began in the field of electronic music.

The first tape recorder for audio was unveiled in the 1930s, and stereophonic sound recordings (which simulates the ‘natural’ hearing process by projecting sound from different directions, ie. Left and right), though first actually showcased as early as 1881 (by French inventor Clément Ader in Paris), was first recorded with in the 1940s. Egyptian ethnomusicologist and composer Halim El-Dabh produced what is commonly agreed to be the first taped composition of music in 1944, in which he used methods such as echo-manipulation and reverberation.

And now we get onto the juicy stuff. Musique Concrète is a method of recording and composing music that consists of taping and raw-sound manipulation, as well as employing synthesizers and other techniques to produce a music that may obscure the source of its original raw material. This type of music was founded by Pierre Schaeffer during the 1940s. Though initially there were some arguments as to the differences between Musique Concrète and Elektronische Musik, the latter of which came into prominence in 1949 upon the publication of Werner Meyer-Eppler’s ‘Elektronische Klangerzeugung: Elektronische Musik und Synthetische Sprache’ (which suggested that music could be created with SOLELY electronic sounds), the two have since blended beyond recognition. A controversial figure in the original electronic music scene was German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, whose wistful and mystical approach to musical composition polarized many in the music and political scenes of Germany. His avant-garde methods produced orchestral and electronic blended work of space and dream-like wonder which changed worldwide perspectives on what ‘music’ really was. Another figure of the group who worked alongside Stockhausen at the Cologne Studio for Electronic Music was Mauricio Raúl Kagel. I am fascinated by Kagel. Not only did the Argentinian-German musician compose some incredible operatic-style works such as ‘Staatstheater’ (1970), which used such instruments as enema apparatus and chamber pots among other bizarre choices of musical ‘equipment’, but Kagel also used theatrical methods in performance that many considered appropriate to compare to the Theatre of the Absurd (an existential style of playwriting which came to prominence during the 1950s in Europe). Kagel would ask his musicians to use specific facial expressions while playing, as well as asking them to interact in peculiar and detailed ways with other musicians and creatives on stage.

Let us stray away from the west and look into the electronic music scene in other countries around the world. We have mentioned El-Dabh of Egypt, but, in Asia, some exciting developments were being made around the middle of the 20th Century. The company Sony was founded in 1948 by Masaru Ibuka and Akio Morita. Various Japanese composers began to make use, following the creation of Sony, of electronic equipment to create music. Aesthetics and music theorist and composer Toru Takemitsu was employed by Sony to utilize their tape recorders to compose music, which was used in theatre, film, and radio. Other composers such as Yasushi Akutagawa, Saburo Tominaga, and Kuniharu Akiyama worked extensively in the field of tape-recorded and radiophonic music in in the early 1950s. Toshiro Mayuzumi, the celebrated avant-garde Japanese composer, was instrumental in pioneering and developing Schaeffer’s Musique Concrète in Japan. Mayuzumi composed more than a hundred film scores, one of which (that for the 1966 film ‘The Bible: In the Beginning…’) was accredited with the prestigious Golden Globe Award for Best Original Score and was nominated for an Academy Award. In 1955, Japanese Government-Owned Broadcasting Company NHK (Nippon Hōsō Kyōkai), which one might compare to England’s BBC, created their own electronic music studio which paved the way for the worldwide electronic music scene. Among other newfound technologies in the music industry, NHK Music Studio was outfitted with ‘tone-generating and audio processing equipment, recording and radiophonic equipment, ondes Martenot, Monochord and Melochord, sine-wave oscillators, tape recorders, ring modulators, band-pass filters, and four- and eight-channel mixers’ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electronic_music#Origins:_late_19th_century_to_early_20th_century).

Let us move slowly back to the west, and back in time. In 1939, John Cage (John Milton Cage Jr., music theorist, philosopher, and composer) created the piece: ‘Imaginary Landscape: No. 1’, in which he used many intriguing methods of music production including speed-variable turntables to create a unique sound. However, no electronic means were used to manipulate the sounds used in the piece. In the 50s, Cage began using the magnetic tape to realize his pieces. Created in Germany in 1928, the magnetic tape allowed music recordings and radio to be reproduced easily and reliably.

Now let’s run ahead and get to what you’ve been hankering for this entire time: the expansion and rise of popular electronic music from the 1960s onwards.

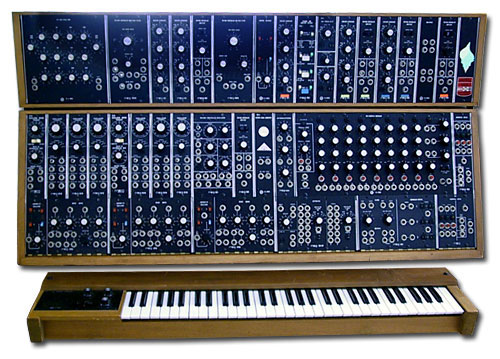

I’m not going to talk too extensively about the more ‘pop’ and ‘rock’-centric people in the game, namely the Beatles and the Beach Boys, because, to me, despite their innovative use of loop-technology and their use of machines such as the theremin, they do not embody the electronic music fervor that I find to be of greatest interest. However, it is worth mentioning the Moog Synthesizer and its revolutionary impact on popular rock and pop in the Western world. Created by Robert Moog, an American engineer, the Moog synthesizer warps and shapes sounds using ‘voltage-controlled oscillators, amplifiers and filters, envelope generators, noise generators, ring modulators, triggers and mixers’ (ibidem). It was the first commercial synthesizer available to musicians and bands of the late 1960s. Interestingly, the Moog was banned from being used in commercial settings because of its threat to musicians hired for recording studios (session musicians) due to its ability to reproduce the sounds of certain musical instruments. For all things Moog check out https://moogfoundation.org/

The Moog was used by Pink Floyd, Emerson Lake & Palmer, Genesis, Kraftwerk, Brian Eno, and Faust, among other progressive rock bands.

Moving more onto ‘dance’-style music: in the 1970s, DJ Kool Herc (Clive Campbell), brought hip-hop music from his native Jamaica to America, transforming dance music culture. Other sound artists such as King Tubby introduced dub music and DJ-focused music creation into the American electronic scene. When the mini-Moog was released in 1970, synth-based music became much more accessible to the regular musician/band, along with the digital synthesizer which was released in 1980 by Yamaha in Japan. Bands such as the Pet Shop Boys popularized dance music and introduced such music-styles into nightclubs all around the world. It was a dance revolution.

Let’s edge onto our last topic of discussion: The Capital of Techno. In case you didn’t know, that capital is widely regarded to be Germany, and, more notably, Berlin (and its close cousin Düsseldorf).

While techno-music itself originated as a definitive style in Detroit during the mid-to-late eighties, after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1991, techno came swiftly over to western and eastern Berlin, where it was played at illegal gatherings and dance parties at various questionable venues (abandoned buildings, basements, power plants, and underground stations, to name a few). The kids of Berlin needed something new, something that belonged to them, something raw and fresh and violent as an outlet for their frustrations and as a symbol of the hardships of growing up in a divided Germany.

In 1992, Reichsbahnbunker or ‘The Bunker’ was opened in a listed air-raid shelter built in Nazi Germany. The Bunker was a hardcore techno-club spread over four floors and became one of the eponymous names associated with the underground techno scene of Berlin. Sadly, the club was forced to close after police raids in 1995 and 1996, and after deliberately unsurpassable building regulations were placed on the tenants of the club. Rather insultingly, the space was bought from the government by a real-estate developer who put on an art festival in the venue in 2002. So…one art-form is more ‘palatable’ than another, one might suppose?

‘Tresor’, an underground techno club which was situated in the vaults beneath the Wertheim department store near Potsdamer Platz in East Berlin, was opened the year before The Bunker, in 1991. It was founded by ‘Ufo Club’ and ‘Interfisch’ (the electronic label) head Dmitri Hegemann, who needed a new venue after the original epicentre of techno and acid raves – Ufo Club, which was actually the first acid house club in Germany – was closed in 1990. What resulted in Tresor was a greatly successful meld of industrial techno music (on the third ‘Tresor’ floor) and more ‘relaxed’ house music on the ‘Globus’ second floor. A record label was also founded by the club during the time it was open. Tresor was closed in 2005 due to issues with short-term renting but reopened in 2007 in a different location.

What has endured throughout the openings and closures of these German nightclubs is a thirst for innovative sound which has brought people from all walks of life together through their love for the alternative music scene.

At Kunstpalast in Düsseldorf, there is currently an exhibition mapping the hundred-year evolution of the electronic music scene from its humble beginnings all the way up to modern day trials with AI musical creations. Düsseldorf itself was the home of choice for such iconic bands as Neu! and Kraftwerk, thus it makes sense that the exhibition, founded by Ralf Hütter of Kraftwerk fame, is situated here. Electronic music, with its intricate, fascinating history, is here to stay, and who knows what might come next.

“Electro. From Kraftwerk to Techno” runs at the Kunstpalast in Düsseldorf through May 15, 2022.

===================

The Carl Kruse Nonprofts Blog homepage.

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

Other articles by Hazel Anna Rogers include It’s Time To Dance!

Our friend and composer Carson Kievman recently died. The Carl Kruse blog covered it here.

No Krautrock? 🙂

All hail Kraftwerk! Still going strong today.

Had never heard of Thadeus Cahill. 🙂