by Fraser Hibbitt for this Carl Kruse Blog

Perhaps nothing more than a remark shared over a lunch established the hypothetical framework for thinking of life extraterrestrial. Enrico Fermi, who was fond of his playful questions (“how many atoms of Caesar’s last breath do you inhale with each lungful of air?”), said, between mouthfuls of the dead, “where is everybody?”.

The physicist’s interjection was nothing new, was ultimately the same bafflement that had sat deadweight on the shoulders of many. Only, when he supposedly said it in 1950, fresh from the success of the Manhattan Project, the rigours of the scientific method found a new room to fill. One could say: we begun to scientifically contemplate extraterrestrial life once we had scientifically discovered how to end all terrestrial life.

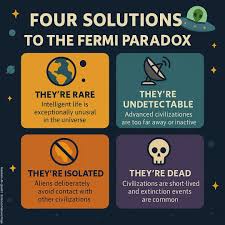

In our galaxy alone, given the vast quantity of planets within habitable life-harbouring zones of their parent sun, and given the vast period of time lapsed, why do we find no trace of life? Or, where is everybody?

God’s silence over our lives, we see no signs, no endgoal, doubles up as our extensions project into space, but the Fermi paradox is not faithful. It is about a form of life that can only be understood by it being civilised, comprehensible, communicable. The hypothetical answers to Fermi really are how intelligent organized life survives or ends. They are psychological complexes over the fragility of life. It is difficult not to think of these hypotheses as contemplations on the limitations of organisation, disguised as exercises in reasoning.

The Beserker hypothesis: self-reproducing machines seek and destroy organic life where they find it and that is why we hear none of the cosmic family; The Dark Forest hypothesis: extraterrestrial life is in abundance, only it is hiding for fear of destruction at the hands of a more technologically advanced society.

It isn’t a stretch to imagine that humanity’s consistent revel in geopolitical conflict underpins the view; it reflects a cold appreciation of human history. The unease of federation, the need for dominance, appear tragic and vain, antagonistic to our higher purpose of understanding, and yet to deny this history-turning need for conflict and the rages of war would be infantile. Arthur C. Clarke imagined a surrogate superintelligence in his book Childhood’s End… a travelling extraterrestrial life whose job it was to transcend civilisations into the universal…These very same extraterrestrials could not comprehend music, could not understand the storm, stress, and resolve of all human life, only that it was time for that stage of humanity’s play to end.

There is an answer to Fermi which, like the Dark Forest and Beserker theory, is more speculative: virtual world isolation. We do not find signatures of life because interest lies rather in divesting oneself of one’s body, relinquishing the frames of physical laws, uploading the mind and tuning in. Once the physical and social environments have been technologically controlled to a suitable level, the embodied mind retreats (or transcends?). We would say now: the constraints of our body and the ethical conflicts it causes are the stultifying aspects of our evolution. Humanity’s aggression could be played out ad infinitum in the cloud, if it chose to develop so, or perhaps it would finally be not needed… society would be as those Tibetan Yogis know the lucid dream.

Many of the hypothetical answers of the Fermi Paradox involve communication, or the lack of ability to communicate effectively: the only detectable signals were broadcasted for a brief period; nobody listens for long enough; no one is broadcasting, only listening; or, perhaps choosing not to listen, actively ignoring.

The science fiction angle runs thus: we can only grapple with the subtlety of things through fiction: our blind actions, self-destructions, and misunderstandings happen without science. A scientist is all very good for the pursuit of knowledge, but is a ‘scientific humanity’ possible? In Tarkovsky’s Solaris, the portrayal of the archetypal scientist is emotionless, dismissive, cold, misanthropic… the ‘life-form’, the planet they are orbiting and unsuccessfully studying, seems to create spectres in those that study it – for the protagonist, it is his love; for the scientist, it is a dwarf. How would we communicate with alien life? Comprehend it? How do we communicate with other civilisations existing on our own planet? We can rear, exploit, care, but have we any idea of them and their minds beyond function? If yes, that would mean ideas are universal despite species, and yet a problem would still lie in the misery of comprehending how to embody an idea. Solaris, amongst other things, throws down the old dichotomy of how we should comprehend the universe: through the spirit (love) or through reason (science). The ending suggests we are stuck in our own mode. The great Polish science fiction writer, Stanislaw Lem, who originally wrote Solaris, thought communication with alien life impossible.

Some have proposed, in answer to Fermi, that intelligence is a rarity, or that intelligence is relatively new. Expansionism, given these facts, would not be the norm. The Great Filter hypothesis states that many insurmountable barriers exist to the attainment of life, preventing many such civilisations from colonizing space. There are many dire hindrances on the way from abiogenesis to a space faring intelligence. We must also accept the hypothesis that it may be the way that intelligent life goes periodically extinct, either at its own hands or by the way of natural disaster.

The Swedish science fiction film, Aniara, portrays the desolation, the immensity, of space. Earth has become uninhabitable and humanity must migrate to Mars. We follow one ship out of many. The three-week journey begins with the feel of an overnight ferry. In the first week, the ship is knocked off its course whilst unsuccessfully trying to avoid space debris, and in consequence its engines are no longer intact. The only hope is to perform a ‘swing-by’ manoeuvre when the next planet crosses their path. In Aniara, hope is flayed down to the bone, is resurrected, and dashed again. The ship has a clear cut of hierarchy which is destabilised by the ever-dwindling hope that a planet will be reached; suicide, ritualistic cults, and a frank nihilism all threaten the fabric, the cohesive harmony, that maintains the ship.

The harbourer of life is assailed and the immensity of space does not provide the elixir to resuscitate it. The original extinctive threat, however, happened long before anyone boarded the ship. Humanity denies and affirms, seeks life and death. The ship was an attempt to breach the threshold of death manifest on Earth.

The fact that humanity could become self-conscious of its impotence to survive and yet doomed to play out this degradation in spite of any knowledge, in spite of knowledge, is the great cosmic joke. The great knock of humility. Yet humanity is a stubborn thing and much of its ingenuity lies in this stubbornness. It is the virtue of life that is has no endgoal, no clear-cut course, and that is also why it proves so elusive and free from the constraints of our reasoning. The ship in Aniara finally reaches a planet. It is in the 5,981,407th year of its voyage. Nothing of human life exists on board. It is a cold dust-filled vessel. And yet, perhaps, some microbe, some bold originator, lives therein, waiting for the eventual crash onto the surface, there to erupt.

====================

This Carl Kruse blog homepage is at https://carlkruse.org

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

The blog often covers issues regarding the Search For Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI), such as SETI1, Frank Drake, SETI2, SETI3, SETI4, and SETI5.