by Alexandra Indra Kruse for this Carl Kruse Blog

The winter solstice is the year’s most dramatic plot twist: the day the sun seems to lose its nerve, hanging low and stingy with light—and then, almost imperceptibly at first, begins its comeback. Long before anyone had weather apps or electric streetlights, this was big news. It wasn’t just a date on a calendar; it was a story your whole village could feel in their bones. The nights were long, the pantry was a question mark, wolves (real or imagined) sounded closer, and the idea that the light might return was both relief and miracle.

If you strip away the modern wrapping paper, the solstice is basically humanity’s oldest annual pep talk: “We made it through the darkest stretch. Now it turns.”

That turning is why so many cultures treated the solstice season as a hinge in time—part fear, part celebration, part bargaining with the universe. In the Roman world, December brought Saturnalia, a festival dedicated to Saturn (an old agricultural god). Saturnalia had the vibe of a sanctioned holiday riot: feasting, gift-giving, and a playful inversion of normal rules. In some households, masters served slaves or everyone wore casual clothes—an intentional, temporary “upside-down” society. It was a way of admitting that winter is chaotic and uncomfortable, so why pretend everything is orderly? Better to laugh at the darkness, toast it, and then escort it out.

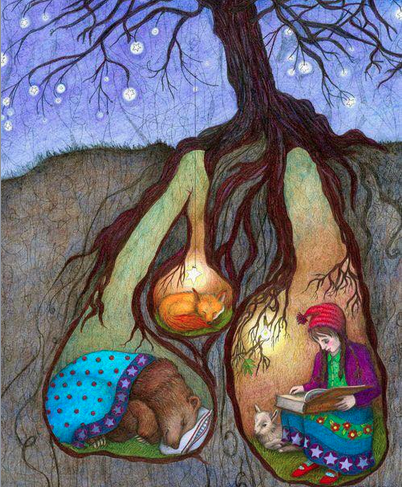

Farther north, the solstice draped itself in the fur-and-firelight aesthetics we still recognize. Yule, in Germanic and Norse traditions, wasn’t a single night so much as a season of midwinter. It included feasts, drinking, communal warmth, and the honoring of ancestors—because when the world outside is cold and hungry, family (living and dead) becomes your fortress. The famous Yule log—a big piece of wood burned to last—wasn’t just decoration. It was a practical spell: keep the fire alive, keep the household alive. A flame in the hearth becomes a tiny domesticated sun, bravely holding its ground.

Evergreens show up in solstice folklore like loyal supporting characters. Pine, fir, holly, ivy—plants that stay green when everything else looks defeated. People brought them indoors not only because they smelled good and looked cheerful, but because they symbolized stubborn life. “See?” the greenery says. “The world hasn’t died. It’s just waiting.” That evergreen symbolism is one reason later winter holidays (including Christmas) adopted wreaths, garlands, and trees so readily—they were already doing the emotional job of the season.

Then there are the monuments and alignments: humanity’s early love letters to the sky. Stonehenge in England is famously associated with solstice gatherings today, and while scholars debate exactly how ancient communities used it over centuries, the broader idea is ancient and widespread: build something that proves the sun keeps its promises. When you can’t control winter, you can at least mark it, name it, and turn it into ritual. A calendar made of stone is a kind of hope you can walk around.

Myths often describe the solstice as a cosmic battle: the sun weakens, the darkness advances, and then—through divine birth, heroic victory, or simple fate—the light returns. You see that theme everywhere: the “dying-and-rising” rhythm, the sacred child, the reborn sun, the triumphant dawn. Even when stories differ, the emotional arc is the same. At midwinter, people want reassurance that decline isn’t the final chapter.

And if you zoom out beyond Europe, the solstice becomes even more delightfully human. In Iran and Persian-influenced cultures, Yalda Night celebrates the longest night with poetry (often Hafez), pomegranates, and watermelon—bright, jewel-like foods that look like edible sunlight. In China and parts of East Asia, Dongzhi marks the season with family gatherings and warm foods like tangyuan (glutinous rice balls), a reminder that togetherness is a survival strategy. In Japan, Tōji traditions include hot baths and seasonal foods; it’s winter self-care with mythic undertones: warm your body, ward off misfortune, invite renewal.What ties these celebrations together isn’t astronomy trivia—it’s psychology and community. The solstice is an excuse to light candles, cook too much food, sing loudly, tell stories, and hug people you pretended you didn’t miss. It’s a seasonal permission slip to be sentimental. Darkness is easier to handle when it’s shared, named, and decorated.

Modern life has tamed winter in some ways. We can heat apartments, import strawberries, and doomscroll under LED lights at 2 a.m. But the solstice still lands. You can feel it in the way cities glow with strings of lights, in the instinct to host dinners, in the urge to buy tiny suns (gold ornaments, citrus, firelight) and place them around your home like protective charms.

And maybe that’s the real magic. The winter solstice doesn’t ask you to be technical or precise—it asks you to notice a turning point. It says: the dark got as dark as it gets, and still the world didn’t end. The light returns not with a trumpet blast, but with a quiet agreement between the sky and time. Humans have been throwing parties for that agreement for thousands of years.

So if you ever need a holiday message that doesn’t depend on any one religion, nation, or era, the solstice offers a simple one: hold on through the longest night. Tomorrow, the story starts bending back toward light.

=============

The Carl Kruse Nonprofits Blog homepage is at https://carlkruse.org

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

The Winter Solstice is often visited here in articles such as this one, and this one, also this one.

Also find Carl Kruse on Pinterest.