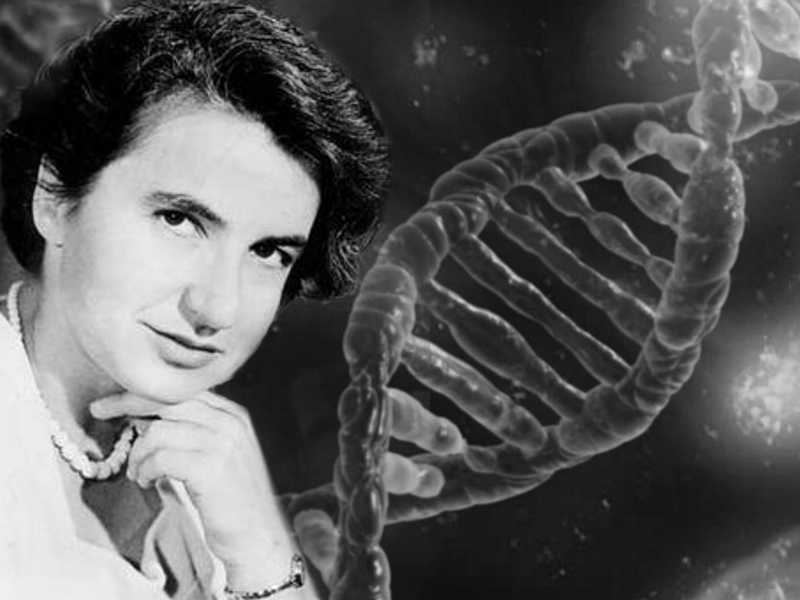

A Tribute to Rosalind Franklin

by Fraser Hibbitt for this Carl Kruse Blog

Every year we here at the Carl Kruse Blog take time to celebrate that moment in April 25, 1953 when Watson and Crick published their findings on the structure of DNA, and of the benefits to humanity that such knowledge has wrought. Our previous celebrations of DNA Day on the blog are DNA Day 2019, DNA Day 2020, DNA 2021 and DNA Day 2023 and this year we join again with all those nerds at heart to celebrate DNA Day.

Our friend and resident writer Fraser Hibbitt gives us a quick background on events leading up to that momentous day in 1953, especially the key role played by Rosalind Franklin. Take it Fraser!

The contemporary consensus is clear: Rosalind Franklin is firmly in place as one of the most remarkable scientists of the twentieth century, finally been hailed as integral to the discovery of the double-helix structure of DNA; it also turns out that James Watson, of Watson & Crick fame, of the double-helix fame, leaves much to be desired, personally. Franklin was a talented X-ray Crystallographer and under her guidance the famous ‘photograph 51’ was produced; the image that was given over to Watson without permission; the image that ‘put them on the right track’ in deciphering DNA’s double-helix structure.

Recent investigation into the period leading up to the discovery shows Franklin as a scientist on even keel with the three who won the Nobel prize for the work they all participated in (Watson, Crick, and Maurice Wilkins)[1]; an initial strain in the working relationships, especially between Franklin and Watson, left the group in an uneasy position. Franklin would die before they had been awarded the prize and for reasons of the Nobel committee (up to three people could win the Nobel at one time; it couldn’t be awarded posthumously), Franklin missed out.

History is always of varying narratives. Franklin had to wait a while for her just recognition from a larger audience, although to those who knew, knew her part was of no small consideration, even Watson thought so at the time; in fact, she excelled at everything she focussed her energy on. Her being snubbed has coloured her popularity; her dying at the age of 37, before wider recognition could be held in her hand only paints the pathos larger. The day before she died, she was to unveil the structure of tobacco mosaic virus; her team member and collaborator Aaron Klug continued in her wake and eventually won himself a Nobel prize in 1982.

Rosalind Franklin carried on in her way. The disagreements with Maurice Wilkins and her director, John Randall, led her from King’s College to Birkbeck university, from the all-important crystallographic work on DNA to working on the structures of viruses. Turning back the time, you find an extremely clever young woman, in fact she always will be, her having not made it to 40; an extremely clever young woman up against an established sexism. Her research fellowship at Cambridge under Ronald Norrish (a later Nobel Prize winner) was marred by jealousies and power plays; an overbearing, obstinate man who couldn’t decide upon an assignment for her to work on. It is of little wonder that she became sensitive over her work, preferring to work alone; and in the annals of history, we see her surrounded by a sea of men winning Nobel prizes.

With the end of WWII, and after gaining her PhD for her work on coal, she found an in-road in Paris through a close friend, Adrienne Weil. It was here that Franklin learned x-ray crystallography under the guidance of Jacques Mering; she held France in her memory as an ideal, a superior land to England; she had a real love for the language and lifestyle. The techniques she learned there would carry her until her death; her infatuation with Jacques Mering was one of the few in her short life. Five years later, she was employed at King’s College, London, and so began the story of DNA.

Since the 1980s, there have been many posthumous recognitions for Rosalind Franklin, from dramatic portrayals to honorary titles. For all that, the narratives of her life, of her personality, continue to defy a simple ‘Sylvia Plath of Science’. A well-travelled woman with many acquaintances; a direct, terse woman of intense eye-contact; a difficult woman to work with; a collaborative woman whose work produced Nobel prize-worthy discoveries; a clouded visage in London, a sunny side in California, and a warm love in France.

Like her headstrong will, the science of DNA continues to march on. Recently, the genes of a mouse were ‘edited’ to create the world’s first ‘fluffy’ mouse; the end-goal is to de-extinct a mammoth from an Asian elephant to populate areas of permafrost: the idea being that these mammoths will save this ecosystem from deterioration; the first mammoth is projected to be de-extincted by 2028. From those pioneers like Franklin, we are coming out from the minute, the microscope, with a power we do not fathom; or, rather, into something of a dream. The strange case of Life haunts itself; self-aware atoms that begin to play the role of creator.

[1] https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-01313-5

The Homepage for this Carl Kruse Blog.

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com|

Also find Carl Kruse at XING.