by Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Nonprofits Blog

He spied an object as he walked along alone in a field, somewhere in Missouri. Perhaps in the town of Hurley where he attended High School. At his school, he played drums as he had done for most of his life. Very early on in his life, His father had taken him to an Arapaho Sun Dance, and there he played a tom-tom on the Chief’s lap. But what could this be but a curious experience for the young boy? He, like many others his age, liked to hit things, often without rhythm, or with a rhythm only they intuit. The young man wasn’t thinking about any of that as he bent over to pick up the object that his curiosity had picked out of the field, out of all else in his field of vision. It would be the last object he would inspect; it was a dynamite cap, and in the play of his hands, it exploded, permanently blinding the sixteen-year old in a flash.

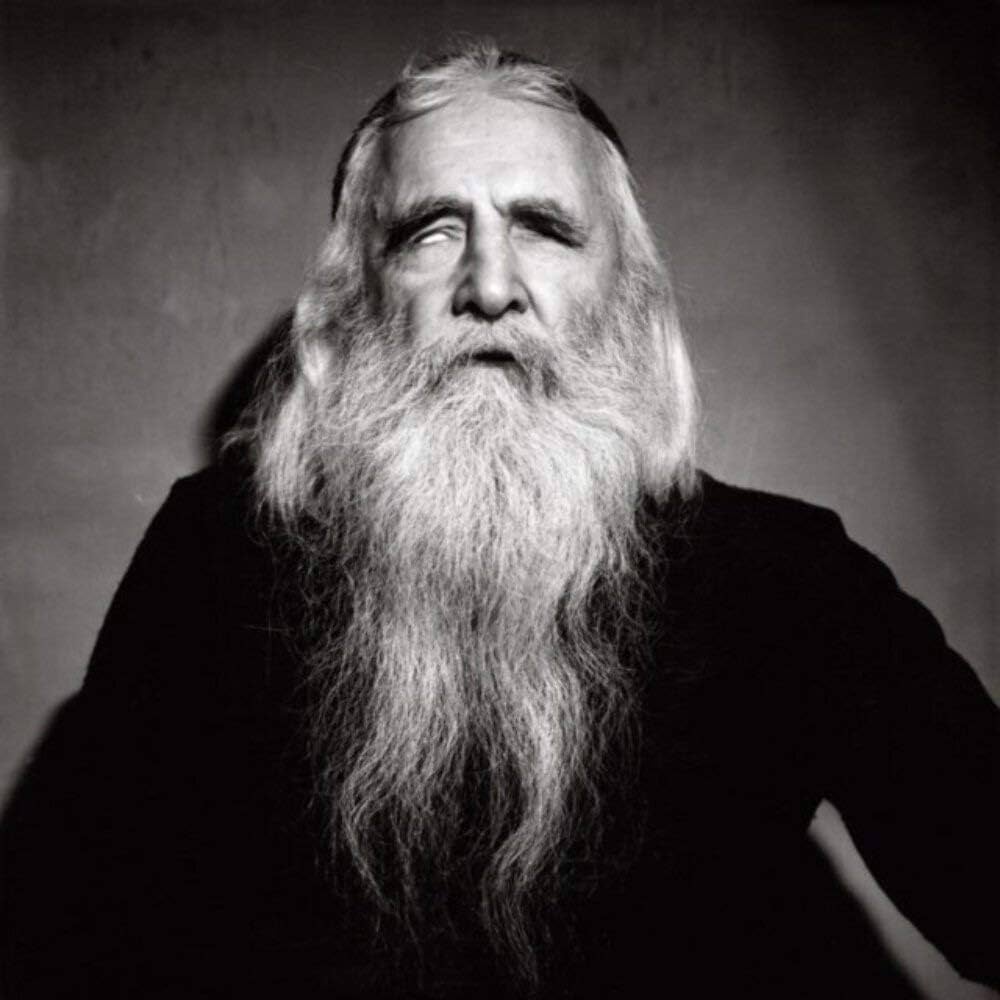

In his blindness, and through his elder sisters’ reading to him, Louis Hardin found the life of music. He found the desire to compose. He moved to New York City and transformed into Moondog. Blind with a long beard and long hair he wore a Viking helmet and played on the street, becoming known by daily commuters. This was 1950s New York and Moondog played the streets and sold his poetry for a living, but he also listened, listened intently; he was composing all the while in his darkness. What did he hear? The sounds of the metropolis; be-bop; He met classical composers Leonard Bernstein and Arturo Toscanini; and, something more, his memories: the rhythms of the Native Americans; later came influences from Modernism, Renaissance, and the various musical traditions of South America.

Rhythm is Moondog’s fascination: “I’m not gonna die in 4/4 time”. And he went about distilling this idea into hundreds of compositions. They are not long compositions; they do not battle their way through the saga of a Sonata; they are a kind of city folk music. The city rhythms that were captured in Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929) forced the director into an experimentalism to capture what happens in a city from when it wakes until the end of day. And it’s no wonder why Modernist artists were so enamoured with the idea of the fragment – the city is a botched puzzle. Moondog’s puzzling is not, however, a jarring one. It first strikes the ear as quite simple, until the counterpoint begins, and the rather simple melodies intertwine like a pedestrian jay-walking through traffic. Moondog once described his rhythm as ‘snake-rhythm’, slithering through the composition, and it’s an apt name for it doesn’t come to the ear immediately.

His preoccupation with rhythm and fascination with percussion led him to construct his own percussive instruments: the timbra is used quite frequently and looks like a mismatch of wood with a cymbal nailed to it but performs in a mesmerising way. You can imagine it there in those second-hand folk music shops as some relic of a distant age, though you won’t because he kept the schematics secret, only divulging the instructions to his only student, Stefan Lakatos, who has now passed away. Of a blind man constructing his own instruments… you can imagine the feel and thickness of the wood, the timbre, the aligning of percussive surfaces: the logistics of the schemata; only imagine, for not working by sight, Moondog was working by an inner ear and tactility. He had, in spite of his eyes, created and placed into the world of phenomena, something uniquely his, of an inner intuition; an inner need for a percussive instrument. And there were many more of which offered an immediate physical ability to reproduce and expand his sound, his desire to translate the rhythmical musicality he heard with such distinction.

Moondog’s idiosyncratic music – he really does not sound like anyone else – remotely. This is an old-time jazz number you think, but it veers slightly off somehow; this is approaching a jazz standard of the depression era, but again it turns. You begin to hear in his compositions the layered counterpoint, weaving, but they do not progress quite a fugue, they are more fractal-like, little melody lines that keep repeating or returning and are more fully realised by another repeating melody that clothes it, all under the accompanying bass and the strange steadiness of snake-time. This idea would later show up in the minimalist work of Steve Reich and Philip Glass who both singled Moondog out as an influence while they were students.

Moondog held among his admirers Frank Zappa, Igor Stravinsky, Charlie Parker… this immediately makes sense considering each’s need to explore music beyond received wisdom. What I would’ve liked to hear is Moondog compose a soundtrack, score a film – it would be a straight story, a simple one yet one elevated by sound, for in light of his idiosyncratic sound, Moondog isn’t harsh to hear, overly complex, only genuinely individualistic. He collected his influences into a ball of his own to play with. “Do Your Thing/ Be fanciful to call the tune you sing” as one of his songs goes.

========================

This Carl Kruse Blog homepage is at https://carlkruse.org

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

Other articles by Fraser include: On my Failure To Write nything About The Music I hear, Winter, and Finally Utopia.

Also find Carl Kruse at an older Carl Kruse Blog here.