by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Blog

She was a thinker, a philosopher, a writer, the first woman to become a psychoanalyst: but more than anything, Lou Von Salomé was a free woman, independent and careless of people’s thoughts. Her magnetism enchanted illustrious figures of the time: from Paul Rée to Friedrich Nietzsche, from Frederick Carl Andreas to Friedrich Pineles, from Rainer Maria Rilke to Sigmund Freud.

Her charm cultivated and inspired some of the greatest minds of the last century. But Lou was not merely a muse, whose beauty and magnetism could inspire others, she was an intellectual force in her own right.

Lou von Salomé was born in Saint Petersburg, Russia, on February 12, 1861, in a mostly male family and was preceded by five brothers. Thanks to the multicultural variety of the family, she spoke fluent Russian, French, and German as a child. And as a child, she distinguished herself for her passion for reading and study, and one of her teachers, Pastor Hendrik Gillot, who did not remain immune to the girl’s charm and, when she was just eighteen, fell madly in love with her. 25 years older than her, he called her “Lou” for the first time. The relationship was conducted clandestinely, but never materialized (Lou wrote that she remained a virgin until the age of 34), however, its conclusion, forced by the intervention of her mother, brought Lou to the brink of a nervous breakdown that risked compromising her health. For this reason, in 1880, looking for a milder and quieter climate, Lou left for Zurich, then moved to Rome, hosted by the writer Malwida Von Meysenbug, who had been forced to flee Germany for her intense activity as a feminist and agitator of revolutionary movements.

Malwida enjoyed acting as a patron to young budding artists: already in 1876, she had hosted in a villa in Sorrento a German professor of philosophy who had been forced to leave the chair in Switzerland for health problems: Friedrich Nietzsche. Nietzsche had brought two friends to Italy, one of whom was Paul Rée, a philosopher born in 1849. Von Meysenbug’s idea was to open and finance an international school for students of both sexes, where the most modern pedagogical techniques would be used, and she entrusted Rée and Nietzsche with the task of organizing and conducting the project. The two, however, never showed much interest and spent their time enjoying Italian life, engaging in research and writing. Rée wrote that at that time Nietzsche had a long relationship with a local peasant woman who visited him at night.

We are in 1882, and Lou Von Salomé, just arrived in Italy, through Malwida meets Rée. Between them there is immediately understanding, they linger in conversations on philosophical issues, but above all on their idea of modern society and individual freedom, leading them to conceive a new model of family, totally innovative compared to that of time, which they called marriage à trois. They decided to put this experiment into practice, and invited Nietzsche, immediately seduced by the girl’s charm. When the two met, Nietzsche told her, “By what stars have we been brought here together?”

The relationship with the two intellectuals was conceived by Lou as cohabitation between kindred minds, yet both men fell in love with her. Meanwhile, Lou’s mother was pressing for her to return to Russia; the three, therefore, did their utmost to extend Lou’s stay to the maximum, setting off first for Northern Italy, then for Switzerland. It was in Lucerne that Nietzsche conceived an idea that embarrassed the other two members of the marriage a trois, but they ended up accepting: it is the famous photo, by the photographer Jules Bonnet, that portrayed them in what was never understood if it was a symbolic arrangement of arcane meaning or a simple joke. Bonnet kept in his studio a cart that he used for skits of country style: on the suggestion of Nietzsche, he and Rée stood at the bar like two oxen, and Lou posed in the cart with an improvised whip. A rather disturbing, but still very iconic image emerged, that the younger of their friends found exhilarating, and the older, including Melwida, scandalous.

proposing marriage to Lou Salomé (the relentless

‘cart driver’). Photographed in the studio of Jules Bonnet in Lucerne in 1882.

After this photo, the three separated, but this did not prevent Nietzsche, still dazzled by the

memory of Lou, to storm her and Von Meysebug with letters, in the hope of a new meeting. After several interferences of Nietzsche’s sister, Elisabeth, who later became famous for tampering with and manipulating her brother’s works to make her sympathize with Nazi thought, the two managed to meet again: but Nietzsche’s love for Lou was not reciprocated by her. Nietzsche, already mentally unstable, slipped into moments of great enthusiasm and great depression and exploded into a kaleidoscope of bizarre behavior: he wrote to Lou’s mother announcing the impending marriage with her daughter, He developed a furious aversion to his old friend Ree when he found out that Lou was looking forward to joining him in Berlin and that he wrote to him every day.

When Lou decided to leave for Berlin, Nietzsche plunged into a deep depression, contemplating suicide. At the same time, Nietzsche began to write his masterpiece: Thus Spoke Zarathustra, finished in 1885, in which references to Lou and their story are innumerable, as evidenced in the most famous biography of Lou “My Sister My Spouse” by H. F. Peters. Later, several scholars questioned the weight of the story of Lou on the genesis of the brain collapse of the philosopher who struck him in 1889, and gradually reduced him to madness, then to paralysis and catatonia, and finally to death, in 1900. Nietzsche is currently believed to have suffered from a brain disease of genetic origin, called CADASIL, which manifests with small but repeated cerebral hemorrhages and ischemia that progressively damage all districts of the brain. The diagnosis is uncertain, however, and is based on the finding that his father and grandfather also suffered from a disease almost identical to his.

Nietzsche was not the only one fatally affected by Lou’s abandonment. Lou and Paul Rée

tried to live together without intimacy for a few more years, until 1884, but their relationship decomposed and ended with the abandonment of Rée, who left without warning, leaving Lou overnight. The two never saw each other again, and Paul Rée was found dead at Celerina in 1901, a Swiss village on the Inn River exactly where Lou and Rée used to spend whole afternoons while they were still together. So his body was found at the foot of a large rock, it is still believed that he committed suicide.

Lou continued her life, regardless of the malicious or benevolent attention of people, in her

independence and her values. Lou was attached to men platonically, attracted by their minds

capable of transmitting knowledge and passion for the world; she was, to use Nietzsche‘s

expression, purely Dionysian, and loved to be so. Her future husband Friedrich Carl Andreas

explained it well:

“She was a Faust in a skirt, not interested in fiddling with empty words. What she

wanted was to discover the hidden strength that holds the world and drives its race: to

know it, to make it her own, to love it.”

But even Andreas did not leave the meeting with Lou unharmed: lured by her, he forced her to marry him, under the threat of suicide. So Lou was slow to make a decision, he put a dagger in his chest to show that he was serious: Lou was forced to agree to the proposal, provided that their marriage remained a white marriage. When they moved in together, Andreas hired a young maid, Maria, who soon became his mistress, and gave birth to two children, one of whom died barely in infancy, leaving Andreas overwhelmed with grief. The surviving daughter, Mariechen, in addition to being the direct heir to Andreas, was also designated the sole heir to Lou’s estate, which had no direct heirs.

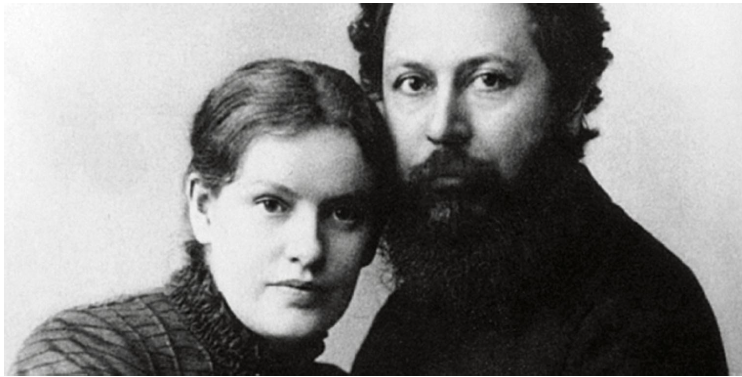

Lou Von Salomé and Friedrich Carl Andreas

The marriage did not prevent Lou from experiencing anything else, but this attitude

towards the physical aspect of the relationship with a man had its roots in an attitude of narcissistic nature, as Sigmund Freud would tell her later: she was enough for herself, and she was implicitly convinced of a conception of woman superior to man, which she did not need. The physical relationship finally arrived with Friedrich Pineles, a Viennese doctor destined to undertake the new bway of psychoanalysis. This change can be explained in Lou’s own words:

“Those who arrive in a rose bush can steal a

handful of flowers, but no matter how many of

them they manage to hold: they will be only a

small part of the whole. However, a handful is

enough to experience the nature of the flowers.

Only if we refuse to reach the bush, knowing

that we cannot pick all the flowers at once, or

if we let open our bouquet of roses as if it were

the entire bush, only then it will bloom

independently of us, unknown to us, and we

will be alone.”

After Pinelas, another mind of the time fell in love with her, this time reciprocated: we are talking about the poet Rainer Maria Rilke. With him, Lou had a turbulent relationship, which lasted for four years, and Rilke took the guise of an addiction relationship. Again, Lou’s abandonment gave rise to the poet’s most important works: Die Aufzeichnungen des Malte Laurids Brigge (The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge) and Duineser Elegien (Duino Elegies). When she left him, Lou wrote to him, “Go meet your dark God. He will be able for you what I can no longer: he can consecrate you to the sun and maturity”. Rilke chose more passionate words, after all, Lou was the only woman he loved in his short life:

“You were the most maternal of women.

You were a friend like men are.

A woman, right in front of me.

And even more often a child.

You were the greatest tenderness I could ever meet.

The hardest thing I’ve ever fought.

You were the sublime who blessed me.

And you became the abyss that swallowed me up.”

When Lou, at the age of fifty, met Sigmund Freud during a congress in Vienna, something in her came out modified. In a way, Freud was also impressed by Lou, but he managed to maintain a relationship of objectivity, in the sphere of pure friendship. Freud wrote about her:

“Those who were closest to her drew the strongest impression from the purity and harmony of her being, and remained amazed at how every female weakness, and perhaps even most of the human weaknesses, remained alien to her or was overcome by her in the course of life”.

Over the years, Lou wrote many books, including biographies of Nietzsche and Rilke, Mein Dank an Freud: Offener Brief an Professor Freud zu seinem 75 Geburtstag (My Years with Freud) and Die Erotik (The Erotic), born from studies, originated from the subjective experience of the thinker, on psychoanalysis. Even if it departed in its founding principles from Freudian thought, (Lou believed that the unconscious was not the bearer of an instinct of death, and he believed in motherhood without procreation) she first explored the psychoanalytic view of sexual and emotional matters concerning the relationship between man and woman, but from a female point of view:

“In love, we feel this urge, different from each other, to join one another precisely under

the impulse of novelty, of strangeness, of something that has perhaps been foretold and

desired but never realized – that does not come to us from the world-known and familiar

to us, with which we have long ago merged and which simply repeats ourselves.

Therefore one always fears the end of a loving passion as soon as two people know each

other too well and the last fascination of novelty has vanished, and therefore the

beginnings of a passion, with its light uncertain and throbbing, are characterized by

such an ineffable charm but also by a particularly stimulating force that deeply upsets

the whole being and makes the soul vibrate – and that later will find hard. Certainly,

from the moment when the beloved object is now only extremely well known, similar

and familiar, but more, at no point, a symbol of possibilities and extraneous life forces,

the real passion is over. After the lovers have revealed themselves to each other in such a

dangerous way, it can also follow a long period of intimate sympathy, but this, in its

nature, has nothing in common with the past feeling and is often characterized, despite

the most sincere friendship, by infinite, tiny irritability. Just what once in a thousand

almost imperceptible traits excited us, now has an even irritating effect, instead of

leaving us at least indifferent, as perhaps happens from the beginning in a friendship.

This is precisely the unpleasant posthumous effect of the fact that it was not something

homogeneous, similar to excite us erotically, but that the monster’s nerves vibrated in

front of a foreign world in which we can never feel at home as in their own, usual daily

life.”

=======================

The Carl Kruse Blog homepage is at https://carlkruse.org

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

Other articles by Asia Leonardi include: Interpretation of Ilness Around the World, Lost Architecture II, and Schliemann’s Discovery of Troy.

You can also find Carl Kruse on Buzzfeed.