by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Blog

The Francis Bacon exhibition in London’s National Gallery comes at a fine time. The world is dying all around and we are beginning to see the skeletal trees beneath the absorbingly great colours of the leaves. Existentialism has been noted for bringing the discussion of death, anxiety, and individualised dread into the realm of philosophy. It is not that these topics weren’t discussed before, only they weren’t discussed with such tangibility, and often in utter scorn of the academic institution; it is obviously easier to consume a scholarly discussion of fear and trembling than it is to experience it, perhaps it works to alleviate the loneliness of it, but it is not easy to read, and in the reading, see your fragility, acknowledge this fear and trembling. Well, death and dread have also always been fit for painting. You can reflect like a good protestant over a Dutch Master who has meticulously rendered a skull and a decaying fruit; you may come out utterly touched by the vanity of this world. I am not saying Francis Bacon is an existentialist painter, whatever that would mean, but I think the comparison helps. He brings death and alienation right up to the door, harshly, rudely.

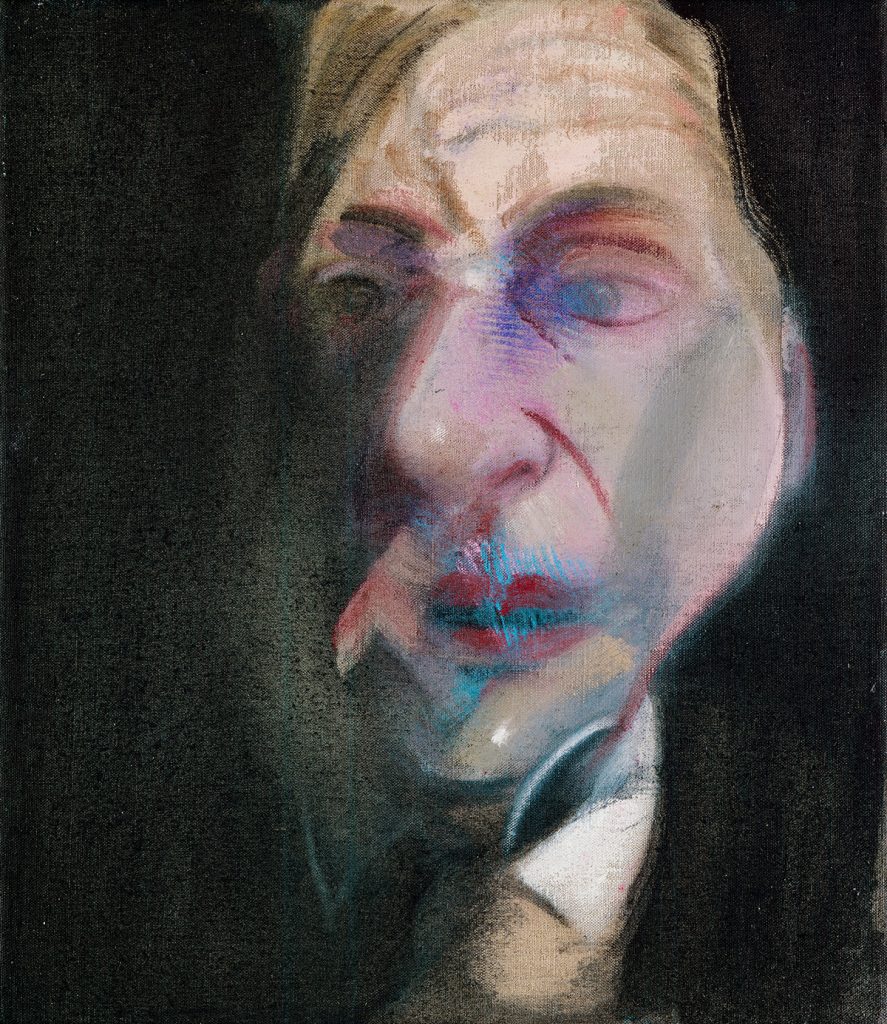

Francis Bacon is obsessed with portraiture and thinks of it in ‘series’; there are the popes on their thrones; the gaping mouths confined to rudimentarily drawn geometric shapes; his friends; his lovers. Often a single subject is laboured over again and again. This is not to clarify anything further, only to reflect a singleness of attention, a kind of love for the human. It is a strange love but a love nonetheless. An unsettling love, but don’t we know it? I hope for our sakes that we do. Commentators talk about these post-war (WWII) artists as real heroes able to confront the horrors of the twentieth century, and I don’t deny them the claim; possibly it’s more interesting to see it unconsciously confronting. Bacon’s friend, and then mysteriously not-friend, Lucian Freud, paints with excruciating detail and precision; Bacon’s head’s are irrupting, the blood and bones burst through the skin, or the skull’s dead grin perches there ready to assume the order of the day. Between these two, you may say, the post-war intensity settles. What is the human figure, now, after this mangled century?

BUT what do we all feel, solemnly walking around the gallery? I was in an excitable mood when I walked in and the exhibition didn’t change that one bit. Grinning occasionally, quizzical the next. I had never seen Bacon before, only ‘second-hand’, and I remembered when I used to sketch these sickly, mangled figures of my housemates and get a kick out of it. Suddenly there were mine in that way. It’s not the same, but I did wonder about Bacon’s pleasure in distorting, doing his ‘injuries’ to his sitters, causing his offence. It is very difficult to capture someone’s likeness, and there is something upsetting with hyper-realism; the presence of that face is always ready to fly out the backdoor. The last piece of the show at the National Gallery is the Triptych of his lover, George Dyer, the night of his suicide in Paris. We see the human mass over a toilet in three stages of disintegration. There is no pleasure in this memorial; this is the death of a lover, the recreation of an event Bacon missed but now re-lives and immortalises. I mention my immaturity and pleasure in re-creating my friends as grotesques for a reason; that was pleasure and play; this is an artist at a height of conception and execution. The subject is altered not for mere whim, perhaps not even for his own emotional processing, his grief. People have been apt to say that art is the redemptive act; in creation, time is somehow stopped, and if time is stopped, the flux, then it is possible to pinpoint an existence…

Excitable after, how? The exhibition is called ‘Human Presence’. Presence, even like a nightmare, still, but presence that melts away the focus of the environment. And, in another way, how joyous is Bacon’s style. Figures faces, his own face, is a dance of brushwork. Always the body recognizably stable, as we see our own, but our own face? Unsettled. Bacon liked this line from Jean Cocteau: ‘every time I look in the mirror, I see death doing its work’. Perhaps I am playing it up as too friendly an occasion. Maybe it’s temperamental, or a kind of respect. Philosopher, or whatever he was, Karl Jaspers said: ‘philosophy as practice does not mean its restriction to utility or applicability, that is, to what serves morality of produces serenity of the soul’, he continues: ‘philosophizing is the activity of thought itself, by which the essence of man, in its entirety, is realised in the individual man’. It may be that art too has such a capability, is such a practice. Why not? I refuse to believe Bacon could paint the death of his lover, and other memorials, without imagining this higher capability. With Bacon, essence and presence combine, both are too fleeting to grasp, hence the ‘thinking in series’… but this is too explanatory… forgive me.

Walking out, you might think, it is neither a celebration or damning of what this thing, popular phrase to use because of sheer confusion: what this thing ‘the human condition’ is? Neither value judgments matter… for now. Who can go into the question without the endless waffle, or the indignant self-righteousness which strangles for a place to land their feet? The point might be merely to communicate – I say merely, but it is no mere thing to communicate. Is communication the more effective for readily giving up its meaning? Yes, if openness of mind is considered worthy. The desire to land solidly on the ground is a different issue altogether; to be fine with a horizon that forever shifts as you move toward it is not only an artist’s progression, but that of our own presence too.

===========

This Carl Kruse Blog homepage is at https://carlkruse.org.

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

Other articles by Hazel include Medshares and A Look at spiritual Capitalism.

Carl Kruse is also on Buzzfeed and on Dwell discussions (Kruse).