Five More Forgotten Avant-Guarde Buildings

by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Blog

From fires to bombings, from building speculation to structural risks, the list of edifices, neighborhoods, avant-garde buildings that we have lost in the course of our history is vast. Sometimes, it was due to unforeseeable agents, causes of force majeure, such as environmental disasters, war, invasions, situations, in short, in which the life and freedom of entire populations were at stake; other times, it was ignorance, superficiality, consumerism: such as, for example, the Larking Building of Frank Lloyd Wright, demolished to give space to a parking lot with only twelve parking spaces.

The etymology of the Italian word ”ricordare” (”to remember”) comes from Latin: re-cor- dare. Breaking it down, we can deduct its meaning from three segments: ”re” (a particle that indicates the act of repetition, which we could translate with the English ”again”), ”cor”, from ”cor, cordis” (literally ”heart”), and ”dare” (”to give”). So, the primordial etymological meaning of the word ” ricordare” is, taking it literally, ”to give to the heart again”. This, I think, is the meaning behind this article: telling a forgotten story, a story built with care and passion, a story that was then demolished, buried, hidden behind layers of cement, bringing with it the dreams and adventures that had fueled the life of the generations that came before us.

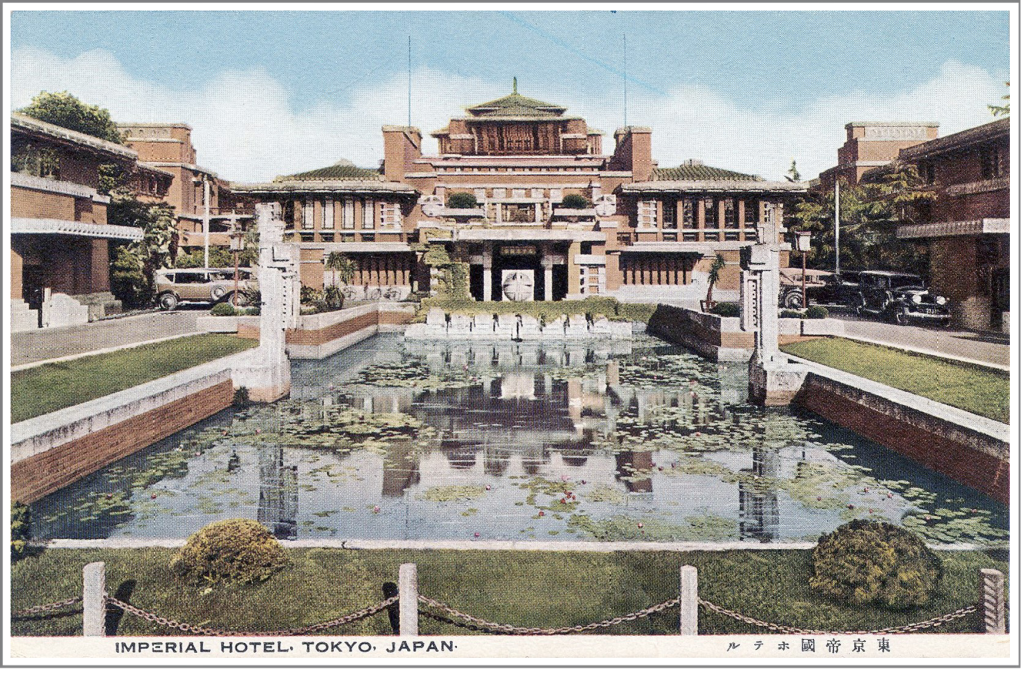

Imperial Hotel, Tokyo

From the moment Franz Lloyd Wright conceived the idea of the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, it was already clear that it was destined to become the icon of a new country: its construction, completed in 1923, was interpreted by many as the metaphorical construction of the new Japan, and, to be fair, the history of the Imperial Hotel was as eventful and dramatic as that of the country. Despite being demolished in 1968, the iconic entrance hall and wing hall were first dismantled, then rebuilt at the Meji Mura Museum in Nagoya.

The hotel construction lasted from 1916 to 1922, involving 600 craftsmen constantly at the work site, and 20 Japanese designers accompanied Wright on the grand project. The American architect, fascinated by the Far East, was already considered at the time a brilliant and innovative mind: in the design of his buildings he knew how to draw great advantages from their location and setting. He considered the buildings “not only a place to live but a way of life”.

The area in which the Imperial Hotel was designed and built, as well as all of Japan, was in constant danger of earthquakes. The ingenious idea of the architect was therefore to “float” the building on the mud, with large and shallow foundations. In this way, Wright explained, the hotel would remain “in balance like a tray on the fingers of a waiter”. The day it was inaugurated, on September 1, 1923, an earthquake struck Tokyo and the surrounding area. Wright was in Los Angeles, and ten long days passed before it was confirmed that the Imperial Hotel was one of the very few buildings that withstood the earthquake.

By 1968 the building had survived several earthquakes, but increasing pollution had caused serious deterioration of the Oya stone sculptures and walls. To make way for a new, larger, and more spacious structure, the management took the painful decision to demolish the iconic Imperial Hotel.

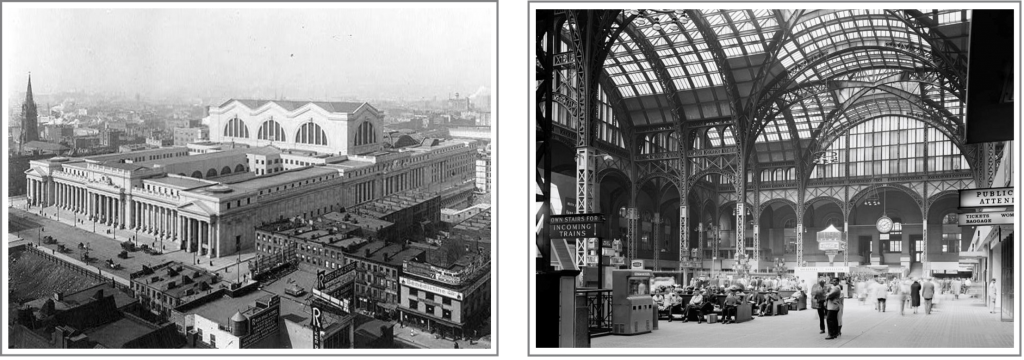

Pennsylvania Station, New York

When it was inaugurated in 1910, the Pennsylvania station was one of the most beautiful train stations in the world: made of marble and pink granite, with a splendid neoclassical style, the station was inspired by the ancient Baths of Caracalla, and it was rich in sculptures and magnificent decorative elements. Unlike today’s station, the original was not built underground, which made its rooms brighter and more spacious. Penn Station was the brainchild of Pennsylvania Rail Road (PRR) to establish a direct rail link between New Jersey and Manhattan. The building comprised two whole blocks, between thirty-one and thirty-three streets at 7th and 8th Avenue; the evocative power it evoked came from the role it was designed for: as gateway to the largest city in the world. But the operating costs for a building of this magnitude became increasingly overwhelming, in particular with the advent of air traffic and the development of the highway system. Penn Station, which reached the 1950s, had lost most of its passengers, and its role gradually waned. The demolition of the building began in 1963, among the many controversies of the day for citizens of the city. However, some of his sculptures were preserved and moved to the entrance of Pennsylvania Plaza.

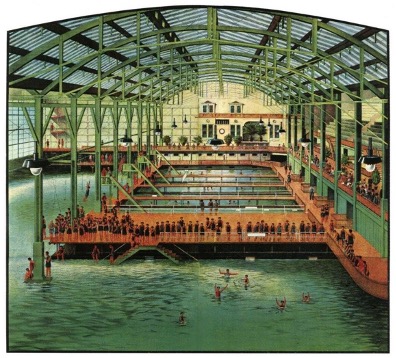

Sutro Baths, San Francisco

In 1894, the mayor of the city of San Francisco, Adolph Sutro, opened the doors of an immense seaside resort, called “Sutro Baths“. The complex included six pools filled with saltwater ocean, a freshwater pool, a concert hall, an ice rink, and even a museum. The mayor’s idea was to offer his fellow citizens a recreational place to spend their afternoons, surrounded by overseas culture: the main entrance housed exhibitions of natural history, sculpture galleries, paintings as well as artifacts from the history of Mexico, China, Asia, and the Middle East, including Egyptian mummies. Adolph Sutro, however, died four years later, and his family took over administering the Sutro Baths, which became increasingly less popular. With the advent of the Great Depression and high maintenance costs, the idea of dismantling the place came front and center for the Sutro family. The complex reorganized into an ice-skating Rink, but served little other purpose. In 1964, the family sold the property to engineers who intended to demolish it and build large scale luxurious buildings, though the project never took place because a mysterious fire that burned almost the entire structure in 1966. Its ruins, now a point of attraction for hikers and tourists, are located in the Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

Crystal Palace, London

It all began in June 1849, during a conference at Buckingham Palace, when a group of British bankers and industrialists urged Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s consort, to organize a monumental exhibition in London, the famous and iconic Great Exhibition. The original idea was to promote local and worldwide sellers, and of course, to promote British industrial products. It is not at all surprising that at the time when Marx composed The Communist Manifesto and The Capital, precisely on the occasion of the Great Exhibition, workers from all over the world joined to create The Communist International. But that’s another story.

When Prince Albert approved the project, immediately a call for applications was issued for an international architectural competition, aimed at creating a large structure that would host the exhibition. The winner, curiously, was Joseph Paxton, gardener, botanist, and architect, who had only distinguished himself until then with the construction of greenhouses.

In just four months, Paxton completed the construction of an elegant glass and cast-iron structure, immediately nicknamed “Crystal Palace”, initially set up in Hyde Park, subsequently dismantled at the end of the event and moved to the center of the great Sydenham Park, in the Borough of Lewisham, where it became a museum and venue for various exhibitions.

The Crystal Palace unfolded in agile and graceful forms, composed of a barrel vault and radial ribs, inspired by the leaves of a nymphaeum, the Victoria Amazonica.

However, the building was not intended to last long: miraculously surviving an 1866 burning, it was destroyed by a fire in 30 November 1936, and the two side towers were demolished during World War II.

Winston Churchill, in a speech in 1936, bitterly commented that the end of the Crystal Palace marked the end of an era.

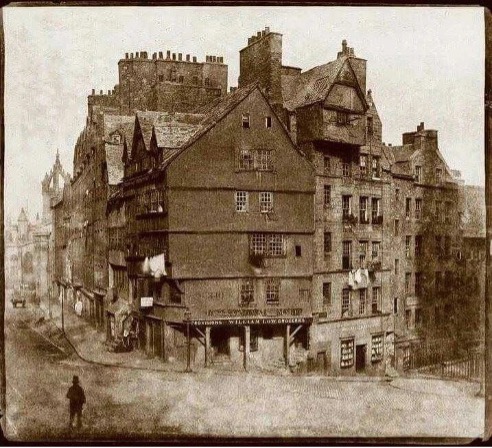

Bowhead House, Edinburgh

If in a past life, on the threshold of the nineteenth century, you happened to pass through the west entrance of Edinburgh, after crossing the Grassmarket, and arrived at the top of a road climbing zigzag, you would be standing in front of a building long known as Old Bowhead or Bowhead House.

The history of this building is doubtful, with many of the records surrounding it having been lost. Built around 1500, we know that it was the property of the newly founded publishing house Thomas Nelson around 1845, and in 1870 was home to the Scottish company William Waugh. Its demolition was noted by James Grant in Old and New Edinburgh:

“One of the finest specimens of the wooden-fronted houses of 1540 was on the south side of the Lawnmarket and was standing all unchanged after the lapse of more than 338 years, till its demolition in 1878-9.”

A newspaper of the time, on February 8, 1878, writes:

“… in a few days, modern improvement will lay its remorseless hand upon the well-known tenement at the corner of West Bow and Lawnmarket. This latter house whose Gables and eaves are richly carved has been long regarded as a most characteristic relic of old Edinburgh. Its quaint timber-framed facade, irregular dovecot Gables, and projecting windows have been a favorite subject of study alike for the architect and artist.”

The Carl Kruse nonprofits blog homepage.

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

The first part of the series on Lost Architecture.

Another article by Asia Leonardi focused on the discovery of Troy.

The blog’s last post covered the Berlin Botanical Gardens.

Discuss green building / design / construction practices with Carl Kruse over at the USGBC

I had no idea that the Penn Station of today in New York City was a replacement of a much grander and older station. Though I understand the burdens of cost and maintenance, I must admit I would have loved to have seen it.

Living in San Francisco I can say you can still see the remains of the Sutro Baths.

I understand why some of these wonderful structures are gone but it still makes me sad.