by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Blog

When talking about progress and development we inevitably recall the scientific advances of Western medicine. And there is no doubt medical technology has made huge steps over the years: in 1900 global life expectancy was about 30 years; in 2000 about 63. Every day, antibiotics save the lives of millions of people, and new technologies and modern diagnostic methods enable doctors to quickly identify the onset of disease.

However, despite what we may think, data shows the risk of coming in touch with a pathogen is much higher in modern societies. This is due to the processes of industrialization, modernization, the unequal distribution of wealth, and the human behaviors associated with them. Large human settlements encourage the establishment and maintenance of germs, as well as pests such as rats and fleas, and also produce large amounts of human waste. Sedentary agriculture also causes landscape alteration that can lead to an increase in the incidence of disease, such as schistosomiasis. Domestication of animals, a characteristic of modern societies, also increases the likelihood of contact with microorganisms that cause disease.

Another element contributing to disease is the distribution of salaries: our body, if it comes in touch with a pathogen, immediately activates the immune system, which mobilizes to defeat harmful intruders. However, the capacity of our immune system stems from our diet, and this is often driven by income. More importantly perhaps, the access to care is often determined by social inequality within a country, and not by the absolute wealth of the country. Looking at the example of the United States, the richest country in the world, we see it rank 25th for life expectancy, below some poor countries.

In looking at different societies, we see that various diseases often have different meanings associated with them, that what are attributed to in the West: magic, witchcraft, the loss of the soul, the possession of a spirit.

Western culture finds many difficulties in understanding interpretations of events other than its own, and the meaning of illness is no exception. However, if we enter into the interpretations of these societies, we can well understand the logical reasoning behind them: the members of the societies that attribute the onset of the disease to a magical act, do not believe that the sorcerer in question acted without a reason; those who believe in the loss of the soul, do not claim that the soul comes out of a person’s body without a reason underlying the process.

They believe, in short, that there is a social reason behind the actions of the magician or wizard: the affected person may have broken a rule of conduct, has offended him in some way, and similarly, the soul leaves the body of a person when he or she has difficult relationships with other members of society, or when he or she does not respect certain social obligations.

The Chewa from Malawi, southeast Africa, believe that disease and death are caused by witchcraft. While in the West our reaction to the disease is to seek the physical cause, Chewa question their social cause: has the victim done something wrong? Did he /she fight with someone? Or maybe some member of the tribe nurtures jealousy against him/her? For this reason, when a Chewa gets sick, they consult a soothsayer to investigate the social causes of his illness. Chewa recognize, more or less implicitly, the connection between disease and social tension, and theirs is ultimately a social theory of disease.

In parts of Latin America some people believe in a syndrome called susto, (also called pasmo, espanto, perdida de la sombra) based on the belief that the soul can leave the body of a person. Symptoms include restlessness, apathy, loss of interest in clothing, as well as loss of appetite and energy. It is claimed that the disease originates from a strong scare, a sudden encounter, or an accident, and the cure begins with the patient meeting a healer to investigate the social roots of the problem.

Susto, as anthropologist Arthur Rubel explains, always originates from a situation perceived as stressful, and stress comes from problems of social relations with certain people. In one case, a father was anxious because he discovered he was no longer able to provide for his family, in another, a mother “lost her soul” because she could not take care of her son in the way she wanted. In any case, Rubel explains, susto occurred when a person could not meet their social obligations. In other words, susto, like witchcraft, is a way to express social tensions and not a simple description of a magical event.

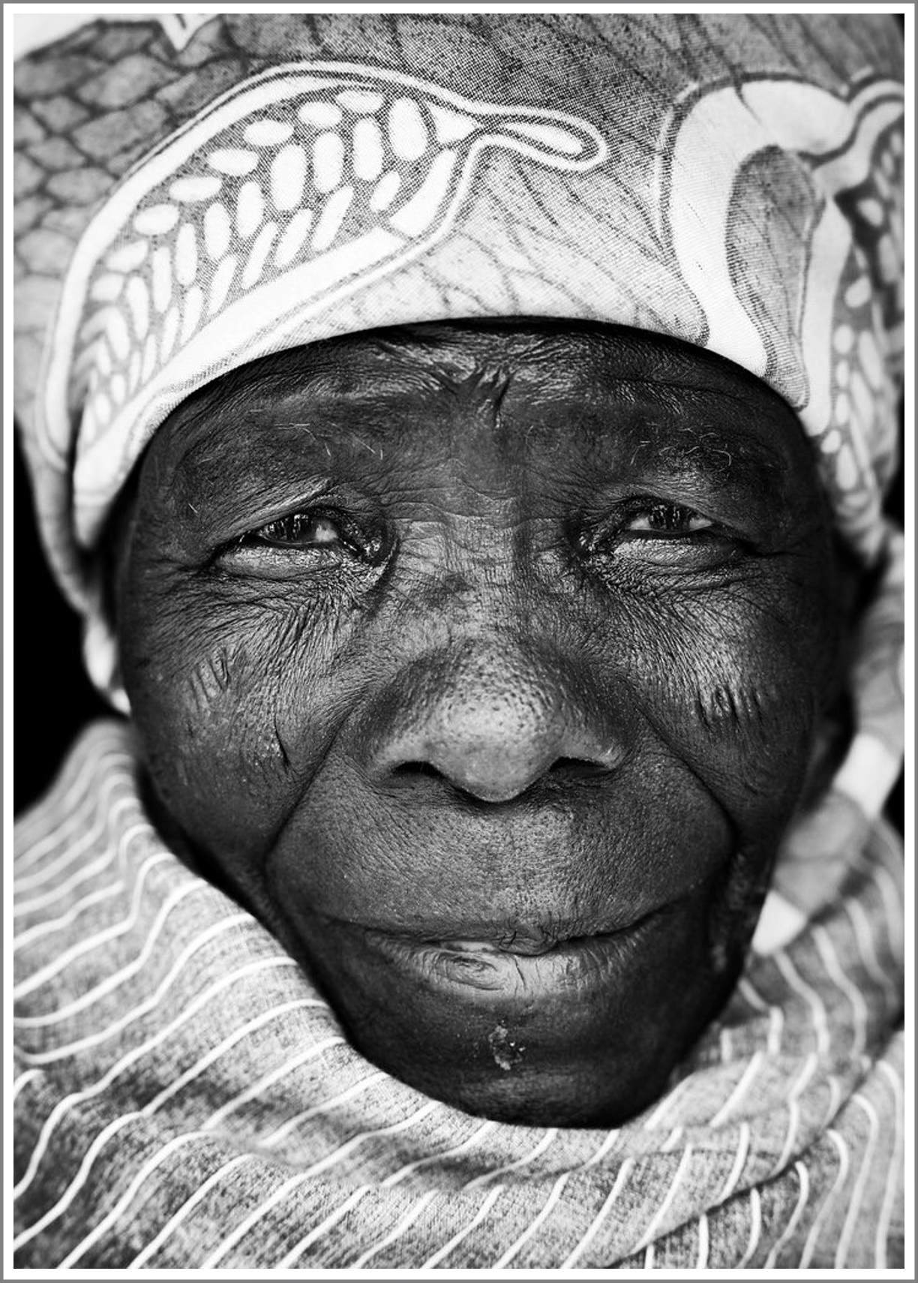

scarification in a remote village near Mitundu, Malawi.

These different interpretations of disease are found in the concept of the interpersonal theory of disease: witchcraft, souls, or spirits are concepts of mediation, like germs, and provide a link between social cause (tension or conflict) and effect on the body (illness or death).

Naturally, if the explanation of the disease is due to a social problem, it follows that the cure must also be, in part, social. Therefore, the healer not only tries to remove a spell or to return the soul to the body but also tries to solve the social problem behind its onset.

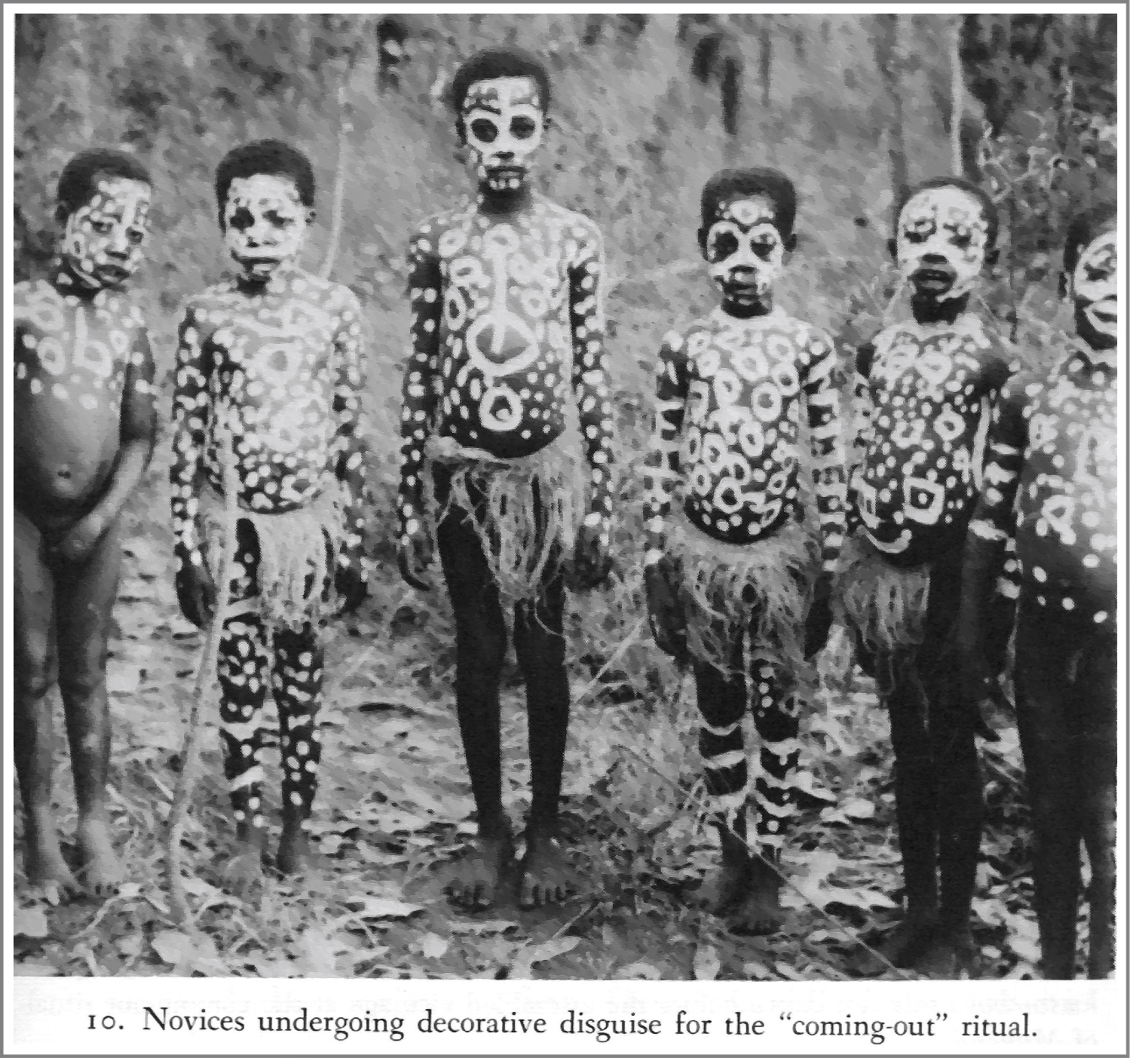

Anthropologist Victor Turner, for example, refers to a case in the Ndembu Society in northwestern Zambia. The Ndembu believe that illness is caused by a punitive action of the spirit of some ancestor or by the occult malevolence of a sorcerer. Spirits punish the living when they forget to make ritual offerings to ancestors, or because “relatives do not live well together”. To cure themselves, the patient visits an indigenous doctor, and together they try to reconstruct the swarms that led to the manifestation of the disease. In addition, the doctor asks people that the patient insulted or with whom he quarreled to attend the ceremony, or a dramatic event, full of pathos, harmonized by songs and drums that can last for hours.

Ndembu, in short, implicitly recognize that stress and social tensions can cause a physical malaise, and one of the ways to cure the disease is to seek and heal social conflicts. Western medical practice has taken a long time to recognize the impact of stress on physical health, but there is clear evidence that some life events can greatly increase the chances of becoming ill. The loss of a spouse, the move to a new home, and even holidays, like Christmas.

While this blog remains a champion for science and all of the progress it has achieved, it would seem that some traditional interpretations of disease — in spite of beliefs that are misguided — could be on to something.

=========

The Carl Kruse Nonprofts Blog homepage is at https://carlkruse.org.

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

Former articles by Asia Leonardi include Schliemann’s Discovery of Troy, Lost Architecture I and Lost Architecture II.

Find Carl Kruse on Soundcloud.

Science it works, bissches.

It does indeed!

Carl Kruse